Vale Albie Thoms

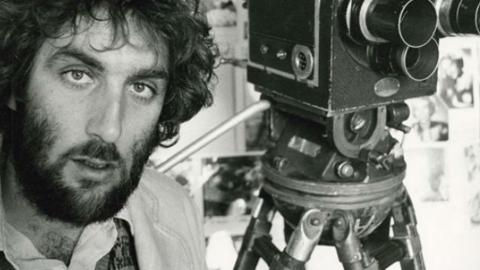

Following the recent death of Albie Thoms (28 Jul 1941 – 28 Nov 2012), Graham Shirley has written a tribute to the Australian filmmaker and advocate for an independent cinema.

In mid-1969 as a young staging assistant, I stood galvanised in ABC-TV’s cavernous Studio 22 at Gore Hill, Sydney, as Bicycle, a live 15-minute improvisation by the electronic group Tully cascaded through gigantic speakers and an Ubu Films lightshow turned the darkness around me into a swirling, multi-patterned, multicoloured happening to redefine everything and everyone every nanosecond. Seated on a tower above the musicians, their faces lit from below as their hands guided cells and dye across light-boxes to orchestrate the lightshow, were the bearded, meditatively absorbed faces of Ubu Films’ Albie Thoms and Aggie Read. They were part of a new departure for the ABC, the electronic music show Fusions, whose original title, Freak-Out, had been changed by order of the ABC’s cautious bosses.

For Albie, Fusions was one event in a decade rich with creative variation, a decade that had begun with the Sydney University Dramatic Society for whom he directed avant-garde theatre, then developed at ABC TV, where he worked for several years as a trainee producer and directed programs like the comedy Nice ‘n’ Juicy (1966) and the action series Contrabandits (1967). There was also Albie’s experimental output for Ubu Films (which he co-founded in 1965 with Read, David Perry and John Clark), including his shorts Blunderball, Bluto and Bolero (all 1967), and his feature-length Marinetti (1969). Albie became involved in the Sydney Filmmakers Cooperative after its formation in 1969, helping to establish its Filmmakers’ Cinema, being a regular contributor to the magazine Filmnews and making his experimental documentary Sunshine City (1973). From 1974 he produced the ABC TV youth program GTK, directed the experimental narrative feature Palm Beach (1980), and wrote and directed mainstream documentaries including Surfmovies (1981),The Bradman Era (1983) and J’OK – The Wild One (1984).

Much else will continue to be written about Albie as an avant-gardist and strong advocate for an independent Australian cinema. But I want to pay particular tribute to him as an historian and archivist. Albie had a love of and desire to communicate history. Hence the above-mentioned documentaries, but also the art history films that were linked to the gallery exhibitions Bohemians in the Bush (1986) and The King of Belle-Ile (2001). In 1987 Albie worked as part of a team, including this writer, to write episodes for The Australian Image (1988), a 13-part documentary series on the history of Australia’s audiovisual media. Albie’s scripts on newsreels and recorded music were exemplars of deep research and well-crafted writing. A few years earlier, he had used his formidable knowledge of the history of 1960s-‘70s Australian filmmaking to inspire me to substantially revise draft chapters on the Australian cinema’s revival in a book that I co-authored, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years (1983).

When I last saw Albie at his Sydney apartment on 27 October, his intellectual energy and enthusiasm were still at full throttle as he told me the stories behind key pieces in his art collection before screening archival films that summed up aspects of his life and career that I’d never seen or heard before. Albie had also lined up a series of boxes in his front hall for the NFSA to pick up when it suited, each one containing treasures in the form of scripts, films and videos of his and other people’s works. As we shook hands when the visit was over, I dwelt on what a true polymath Albie was – somebody who had not only immersed himself in alternative ways of looking at cinema, but who had also been part of the mainstream as a filmmaker, historian, theorist, educator and a force for change.

Albie Thoms passed away at home in Sydney on 28 November 2012. On Monday 17 December, a celebration of Albie’s life will be held at the Paddington Town Hall, Sydney.

Cataloguing the work of Albie Thoms, by Roslyn Barker

In 2009 the NFSA received the material relating to the Albie Thoms collection for cataloguing. The Collection Information team sorted, organised, catalogued and packaged more than 8000 individual works such as scripts, photographs, posters, videos, films, correspondence and papers relating to his involvement with the Sydney Filmmakers’ Co-operative.

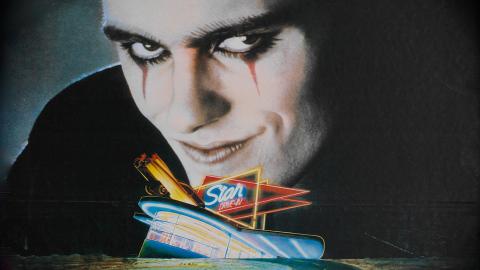

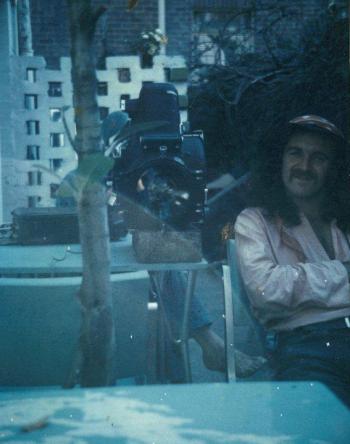

I remember sorting through a jumble of photographs relating to the film Palm Beach, which was directed by Albie, and making sense of what I had. I particularly remember a set of production images.

These were shots from the film, some of which were taken in Manly, NSW. I had spent time in Manly in my younger days and could identify exactly where the shots had been taken, in the Manly Corso. It was very interesting to see the images and know that my aunt lived in a flat just above where the action occurred. I also cleared up some identification issues with some of the actors in the photographs by watching sections of the film on australianscreen.

Albie was pleased that his papers and other works were being described and sorted, and preserved in the national collection. During this process he visited us in Canberra and we were able to discuss any problems we were having regarding identification or other issues. It was great to be able to meet him and have first-hand information from him. After the works were all catalogued and available to be viewed on our Search the Collection facility, Albie sent in a number of emails to clarify or add further information to the records. The CI team enjoyed working closely with him and it was a satisfying experience to be able to meet and talk with the donor. It doesn’t happen often.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.