NFSA Librarian Jan Thurling takes a look at the local film critic scene - from Australia's very first review, to the new generation of critics.

NFSA Librarian Jan Thurling takes a look at the local film critic scene - from Australia's very first review, to the new generation of critics.

Australian film criticism started with an anonymous review in The Age in August 1896. It read: ‘The cinematographe, which was introduced to Australians by Carl Hertz at the Opera House on Saturday night, must be ascribed a leading position. It is a combination in which the effects of the kinetoscope are imparted to limelight views, producing scenes of amazing realism, and giving them all the characteristics of actual moving life.’

According to NFSA Historian Graham Shirley, surviving examples of early film criticism are important because they can provide essential information on lost films, including details about plotlines, cast, crew and actors: ‘They will, irrespective of whether a film survives or not, provide insights into critical and more general social attitudes of the film’s era. Even if a film does survive entirely in the form in which it was intended to be seen, a review enables the current reader to compare the critical value systems of earlier times with those of today. Reviews also provide a window on how cinema as a medium, and specific national cinemas were regarded at the time a film was made.’

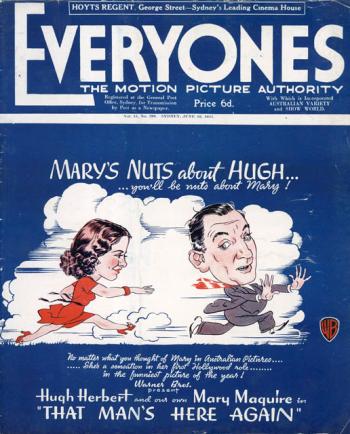

The NFSA Library holds collections of over 100 Australian film publications dating back to the 1920s, and including film journals, newsletters, magazines and trade papers. We have a regular stream of researchers and members of the public exploring these publications. They can trace the development of Australian film and the careers of local filmmakers, discover how films were received, and examine the concerns, and trends that have followed the development of local film production right up to the present. I love hunting through the collection myself! Here’s an example that I’m sure all film lovers will enjoy: four pages full pages from a 1933 issue of The Film Weekly.

The Australasian representative of Gaumont-British Corporation fnfilms a deal with Fox Film Corporation.

Newsreel highlights for July 1933.

The week's film reviews, including "Waltzing Matilda"

"Waltzing Matilda" will "set a new standard in Australian Film Production".

Local film criticism soon expanded to trade publications, film society newsletters and fan magazines; then radio, television and now online. There are more than 120 film critics in Australia today – working across all types of media, analysing and informing Australians about our own films and world cinema. Australia has two very active bodies promoting film writing: the Film Critics Circle of Australia (FCCA) and the Australian Film Critics Association (AFCA). They promote excellence and expertise in film criticism, and through the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI), add Australian voices to film commentary worldwide.

Film writing has always been important to the development of Australian film culture, providing us with our own film context and history, and creating an audience for local product. While Australian film is only four to five per cent of total box office, it is still a significant industry. Australian films earned $50.6 million at the box office in 2010.

Reading through some of the material the Library holds, I discovered a lot of commentary between critics and the industry over their role and their effect on local box office performance. While the true effect, positive or negative has not been quantified, for smaller independent films without a marketing budget, even having a few film reviews in the public domain gives the film a prominence which might increase attendance. While big local films like Australia (Baz Luhrmann, 2009) are considered critic proof, the work of film critics definitely affects the reception given to smaller, independently marketed films.

Can negative criticism harm Australian films? It seems that the critics themselves believe so. Some believe that Australian films should be treated just like any other, while others refuse to review films they don’t like. In a 2004 Metro article critic Peter Thompson said: ‘I feel very strongly about treating creative people with respect and if a film doesn’t work in my view, I would rather keep my opinions to myself.’ In the same article critic and ASO curator Paul Byrnes says that ‘if you apply different standards to an Australian film you’re not doing the film any favours. You’re responsibility as a film reviewer is not to the filmmaker, it’s to the reader.’

Peter Krausz, Chair of the Australian Film Critics Association told me: ‘AFCA do try to give an extra lift to Australian films, but that doesn’t mean that we won’t mention anything negative. We believe that Australian films deserve the same criticism as any other films. While we go out of our way to make sure all Australian films are reviewed, and will be a little kinder or sympathetic, we will still review negative aspects. If we don’t have an Australian film industry and Australian film culture then we are completely lost. But we encourage good films, and encourage the industry.’

Australian filmmakers seem to understand the importance of criticism to the industry. While large Hollywood studios often try to by-pass film critics, spending vast sums creating a publicity machine to drown out any negative comments; Australian filmmakers welcome critics who can help audiences understand films which are not automatically appealing, and which might be challenging to audiences used to straightforward genre filmmaking. Film critics encourage audiences to see films, and make up their own minds.

So, should we fear then, the effects of recent reductions in print criticism? There are definitely fewer film critics in major magazines and newspapers; and those that remain are often syndicated and republished, giving audiences access to a smaller number of voices. Perhaps not; it seems that despite current challenges, Australian critics still fare better than their US counterparts. As well as a shrinking market, American film criticism had a major scandal in the last few years, when it was discovered that a film studio had created a fake critic. This fictional critic wrote glowing reviews for Columbia Pictures for a whole year before the ruse was exposed. Thankfully we don’t have any fake critics here in Australia!

But do we have any young critics? Most prominent Australian critics are over 40. Of AFCA’s members there are only 5 aged under 30, and only 12 aged between 30-40. Film criticism is a difficult field to break into. Age brings experience, and the encyclopedic knowledge of film, history and culture that makes for a good critic. So should we be worried about the scarcity of opportunities for younger critics? The Australian Film Critics Association (AFCA) certainly recognises it as a problem. They contact the next generation of film critics through universities and other institutions, encouraging new writers to join as associate members, and giving them opportunities like the young film critics placements on FIPRESCI festival juries.

All in all, it looks like the Australian film criticism is alive and well, and I would like to send my thanks to all the critics out there who are educating Australian audiences, encouraging them to experience all the diversity of cinema, and creating a record of Australian film culture for my future researchers.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.