Bert Ive

Graham Shirley traces the history of the Cinema and Photographic Branch through the life of its first long-term cinematographer, Bert Ive.

Bert Ive was not a name that I knew much about until I worked on a project on the history of Film Australia in the early 1980s. Working with me was the highly knowledgeable Film Australia historian Judy Adamson, and to help the two of us flesh out the early history of government filmmaking, Judy had access to Bert Ive’s scrapbook and his work diary. The scrapbook was crammed with information about every aspect of Ive’s film career from 1906 until the time of his death in 1939. It is substantially from that source, now held by the NFSA, that I have drawn the following information about his life.

Albert Sewell (‘Bert’) Ive was born in Reading, Berkshire, England, in 1875, to William and Ellen Ive, and was introduced to cameras and photography as a child. At the age of 11, he and his family moved to Australia, where they settled in Brisbane. Leaving school at 13, Bert Ive trained as an artist before working as a glass embosser, sign-writer, decorator and painter. He was on stage as a live entertainer in 1896, and the next year was entranced by his first viewing of film. He became a travelling film exhibitor through south Queensland and northern New South Wales, and by 1906 was projecting films and song slides for Ted Holland’s Vaudeville Entertainers in Brisbane. In 1909 he shot his first actuality film, after which he alternated actuality and feature film camerawork with film exhibition. In May 1913 he was appointed the Commonwealth government’s cinematographer and still photographer.

This position had previously been held, from December 1911 to May 1913, by James Pinkerton Campbell, but for reasons including personality clashes, arguments over quality and the under-resourcing of Campbell’s work, this appointment had not been a success. By contrast, from the moment Bert Ive commenced in the role, he was encouraged to set up what would eventually be known as the Cinema and Photographic Branch. His first months in the job involved establishing a Melbourne workspace and buying equipment, and in March 1914 the Brisbane Star newspaper reported that he had ‘spent six months travelling around the States taking living pictures of anything of interest’. Other newspaper reports described Ive as ‘an enthusiast’, ‘a man of infinite resource’ and ‘of a happy nature’, and these qualities, along with the promotional nature of much of his work, usually guaranteed him a ready welcome wherever he travelled.

From 1913 to 1939, Ive’s activities were administered by a succession of eight federal departments, including External Affairs, Home and Territories, the Commonwealth Immigration Office, and the departments of Markets and Commerce. These attachments meant that the central purpose of Ive’s work changed a number of times, ranging from the promotion of Australian goods, tourism, national development and national awareness, through to encouraging migration, especially from the UK.

Throughout his career as government cinematographer, Ive was also expected to record for posterity such pivotal events as the departure of the first AIF convoy for Gallipoli, the royal tours of 1920 and 1927, and the construction of Canberra, Australia’s east-to-west transcontinental railway and the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Alternating his work between home base in Melbourne and travel by car, truck, train, aircraft, boat, camel and on foot, Bert Ive also criss-crossed Australia to film regions, towns, communities, industries and tourist destinations to publicise the nation for audiences at home and abroad at a time when many Australians had not yet explored their own country.

After its transfer to the Commonwealth Immigration Office in 1921, the Cinema Branch’s facilities and staff were expanded, and by 1930 its staff of 14, coordinated by a production manager (Ernest Turnbull from 1924, Lyn Maplestone from 1926), included Bert Ive, second cameraman Alf Watson, writers, editors, laboratory staff, and people who maintained the branch’s film and stills stockshot libraries.

By the end of the silent era, the Cinema Branch turned out a new film every week, and many of Bert Ive’s films were released under the collective titles Know Your Own Country and Australia Day by Day. In 1929 Ive and Lyn Maplestone appeared in Telling the World, a documentary about the Cinema Branch itself, and in 1930 the branch made its first sound film, This is Australia. Cinema Branch films of the 1930s to be given an Australian and overseas release included The Heart of Australia (Central Australian travelogue, 1932), The Air Road to Gold (New Guinea’s gold fields, 1933), Tight Lines (big game fishing, 1937), and Among the Hardwoods.

The first Bert Ive film that I ever saw was Among the Hardwoods (1937), a lyrical documentary he had filmed in the south-west of Western Australia. A total remake of a silent documentary that Ive and Lacey Percival had shot for the federal government’s Know Your Own Country series in 1926, the sound version improved on the original in several ways.

Compared to the utilitarian ‘industrial’ feel of the silent, the new version showcased a succession of classic images that took time to absorb the atmosphere of the forests of Western Australia’s Pemberton region, and the work of the timber-getters who felled, transported and milled gigantic jarrah and karri trees in those forests. Where the original had over-explained with too many intertitles, the 1937 version lingered to advantage on comparatively few images and titles, accompanied by the natural sounds of the region. That Lyn Maplestone, who directed both films, was able to improve on the original was due in substantial measure to Bert Ive as cameraman.

Modest budgeting and rapid output meant that few of the branch’s films achieved the artistry of the 1937 Among the Hardwoods. Many others, such as Conquest of the Prickly Pear (1933) and promotional films on Australian eggs, apples and sugar, can be judged today as routine ‘product’. But given the chance, as was also the case with Through Australia with the Prince of Wales (1920), Bert Ive could create an engaging, enduring work. Filmed during the prince’s Australian tour of May to August 1920, Through Australia recorded the prince’s journeys to cities, small communities, factories, farms, war memorials and sports grounds to thank Australia for its contribution to the First World War. The film showed the easy rapport the prince developed with servicemen and ordinary people, and occasionally there are hints in closer shots of the exhaustion the prince appears to have felt on such a lengthy tour.

Ive also showed his mastery of grandly composed epic images, such as wide shots of the prince riding through a lavishly decorated, crowd-packed Sydney CBD, a motorcade past numerous welcoming children and soldiers in Launceston, and tracking shots through masses of Newcastle steelworkers, a cityscape of smog-shrouded blast furnaces towering into the background. With Through Australia with the Prince of Wales, Ive created an all-embracing portrait of the nation and its close links to Britain, a type of film that would not recur until the Stanley Hawes-produced The Queen in Australia (1954).

Bert Ive died on 25 July 1939. Two months later, after Britain’s and therefore Australia’s declaration of war against Germany on 3 September, the Cinema Branch was made part of the federal government’s newly created Department of Information, which in 1940 formed a Film Division to mobilise film for national ends. Soon after Ive’s death, the Townsville Daily Bulletin called the film heritage he had shot for Australia over a quarter of a century a monument to his ‘energy and vision’. This heritage, which was passed on to the Cinema Branch’s postwar successors, the Film Division, the Commonwealth Film Unit and Film Australia, is now part of the Film Australia Collection at the NFSA.

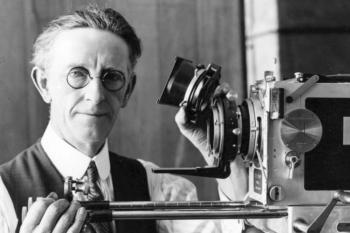

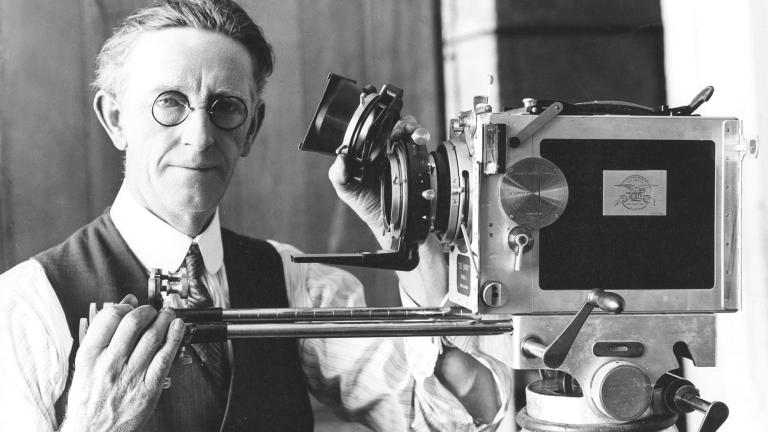

Commonwealth cinematographer Bert Ive in studio holding a lens component next to a Debrie camera.

Commonwealth cinematographer Bert Ive, inserting a rack of film into a drying rack, at the Cinema and Photographic Branch.

Commonwealth cinematographer Bert Ive standing in a Tiger Moth aeroplane. There is a camera strapped to the plane and a pilot is seated in the front.

Cinematographer Bert Ive standing with four Aboriginal stockmen beside a utility truck. The truck contains essential items such as film equipment and water tanks required for long outback trips.

Commonwealth cinematographer Bert Ive, standing on a lugger behind a camera on a tripod, in between two pearl divers, during a nine day trip out from Broome in 1929.

Cinematographer and film exhibitor Bert Ive (far right) standing with projectionists and film projection equipment outside Centennial Hall in Adelaide Street, Brisbane. Photo taken in early 1910s prior to his appointment as Commonwealth cinematographer.

Cinematographer Bert Ive is standing on a garden path by Torrens Lake in Adelaide in 1929 with his camera on a tripod.

Commonwealth cinematographer Bert Ive standing in a field of native flowers, behind a Debrie camera on a tripod, with a stills camera slung over his shoulder.

The workroom at the Cinema and Photographic Branch. Cinematographer Bert Ive is on a ladder using the titles camera. A man below him positions cut-outs while other people can be seen touching up photographs and editing.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.