WARNING: this article contains names, images or voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

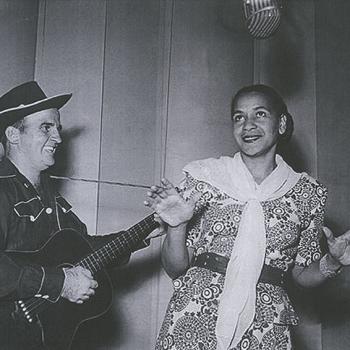

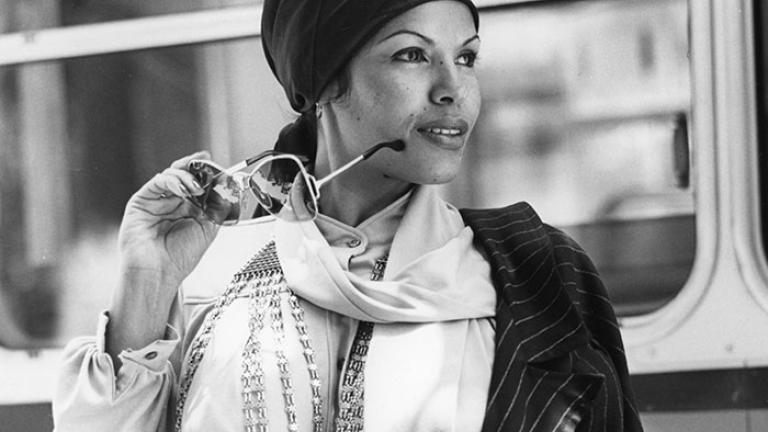

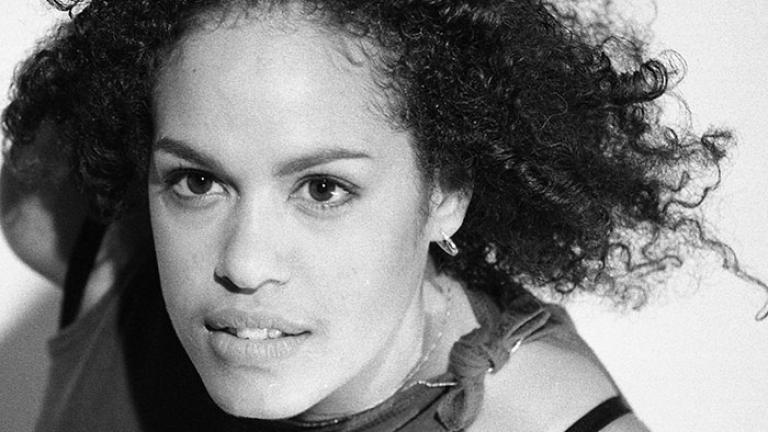

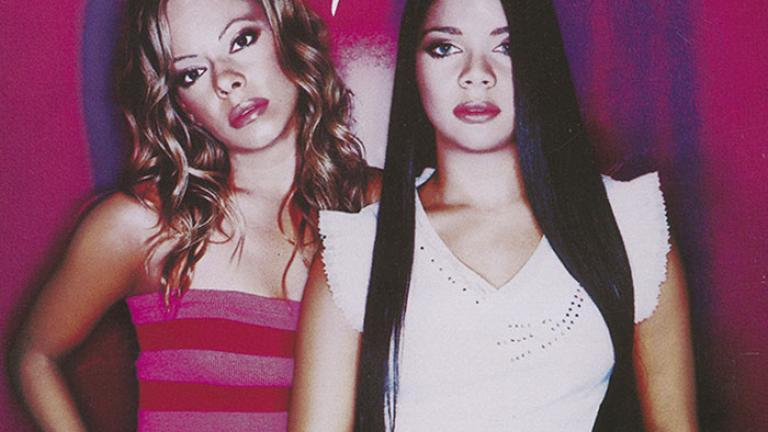

Sophia Sambono, Curator Indigenous Collections, surveys the black and deadly women of Australian music, from Fanny Cochrane Smith in the 1890s to Jessica Mauboy in the 21st century.