Bringing records back to life

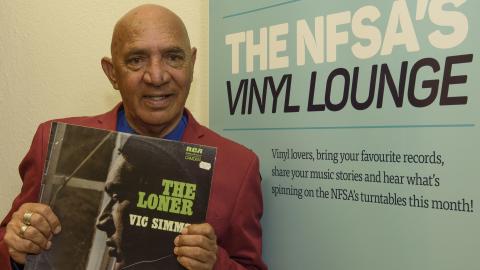

Gerry O’Neill is an audio expert, working in the NFSA’s Preservation and Technical Services department.

We interviewed him in the lead up to our Digitise or Perish forum because one of his talents is preparing different kinds of discs for digitisation, to ensure the sounds they carry survive beyond the shelf life of the physical materials in which they are contained.

What are the steps in the disc cleaning and digitisation process?

If the discs have a lacquer coating and are not cracking, or if they’re made of shellac/vinyl, I can dip the discs into a sonic bath which sends a pulse through the chemically-infused water. The sonic motion dislodges dirt, mould and other particles from the surface of the disc and from within the grooves.

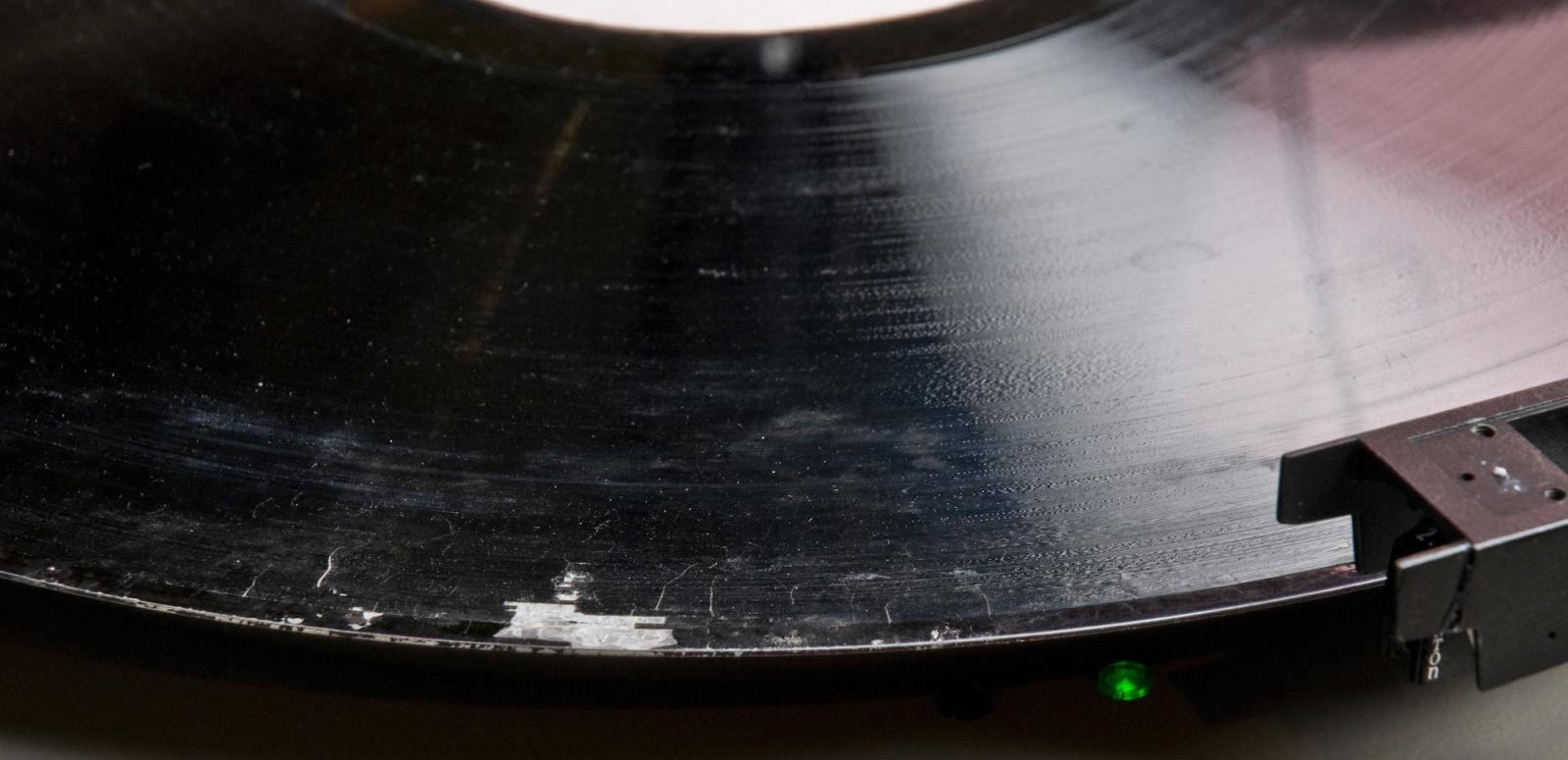

Once the disc is on the turntable and if the quality is still quite rough, I can try a method called wet play. I squirt chemically-infused water onto the disc while it’s spinning, and then play the disc. This allows the stylus to flow through the terrain of the grooves more smoothly, and cuts back the crackle, scratching and pops.

When the record has been digitised, I then assess the visual wave form displayed through software. At this stage, I have the ability to remove hiss, pops, crackles, scratches and certain frequencies, and shape the sound to increase the signal and lessen the amount of noise.

Gerry O’Neill cleaning 16-inch transcription discs. Photos by Darren Weinert.

Cleaning a transcription record

Cracks on a transcription disc

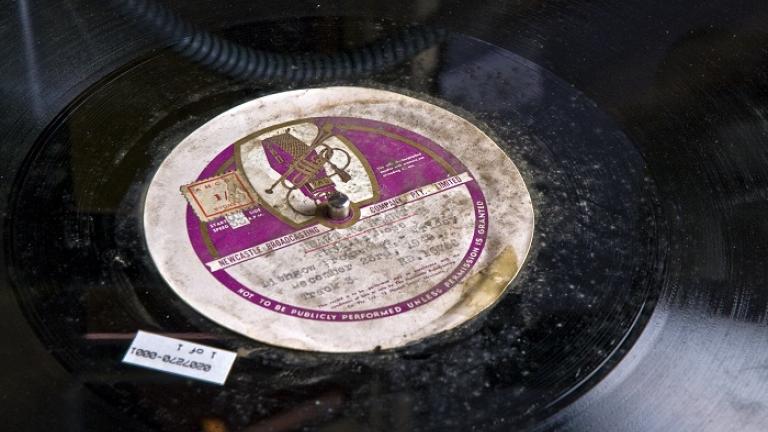

Heart to Heart transcription disc

Damaged transcription disc surface

Damaged transcription disc edge

Zooming in on the disc's grooves

Ready to be digitised

How would you describe the condition of the transcription records seen here? Surely you’ve seen better, but have you seen worse?

The condition on the edge of these transcription discs is poor, but the majority of the disc surface is not as bad and still tracks quite well.

I have worked with much worse, particularly with lacquer discs where the lacquer has become very brittle. When a stylus is moved over such fragile lacquer, it tends to dig under any cracks and lift the lacquer up, which makes pieces chip and fly off in all directions. If you can imagine crazy paver patterns, lacquer on most occasions tends to crack and separate like that. If the separation gets too wide and begins to lift too much, then it may be best to hold the tone arm so that the stylus is connected to it, and try and extract the information groove by groove by holding/hovering the tone arm – although this is very time-consuming!

There are a few cracks on the edge. Is that part of the disc ruined forever, or can it still be played?

If a piece of lacquer is missing then it’s gone forever and that segment can’t be reproduced; however, because these discs spin at a certain speed, the loss of information is minimal depending on the size of the segment missing. The stylus still has the ability to land into the coinciding groove, although sometimes it may require me to guide the stylus by hand to help it land in the correct groove.

The cracked lacquer sections can still be played through but again, they may not always join the corresponding groove which means I will guide it into place. When the stylus drives through cracked lacquer it creates a popping/crackling sound which is removed later using various digital filters once the raw transfer has been dubbed into the computer. When the stylus travels through a missing segment, the sound could be described as a thump with white noise.

What is that machine you’re using?

It’s a Heerbrugg microscope to zoom in on the grooves, to assess groove depth in order to choose what size stylus to use. I also use the microscope when piecing lacquer flakes back onto a disc, when they’ve become dislodged. I can then align the grooves so the stylus can track. I use the same microscope and similar techniques for broken wax cylinders as well.

For a moment I thought it was one of those laser machines that ‘play’ discs without touching them…

No. Those are laser disc scanners that scan the record groove by groove, and interpolate the scanned information back into audio. They’re currently the best known non-invasive way to read a record, but the technology has not quite caught up with how to deal with broken discs and cracking lacquer discs. Every year new technologies are coming out and we have been watching closely to see when our methods become obsolete and the new tech methods are the way to go.

Listen to the digitised disc:

Heart to Heart (1949). A women’s session (radio program aimed at women) presented by Phyllis Rose heard on 23 December 1949. Rose reads letters from listeners and discusses the topics raised. Listeners are asked to send their letters to their local radio stations of 2LT Lithgow, 2HR Maitland and 2KO Newcastle, where the program was produced. NFSA title: 207270

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.