British Film Noir

Generally defining where film noir starts, stops and what it is – and perhaps more importantly, what it isn’t – is hard enough. Getting what’s specifically film noir in British cinema is even more elusive. This is even if we narrowly stick to when it was most likely to have happened: postwar, between 1945 and the arrival (at the start of the ‘60s) of British cinema’s much better known ‘kitchen sink’ realist filmmaking movement.

We are dealing with a genre heritage amongst whose interesting characteristics might be that it’s long been assumed not to exist – a suggestion from a pioneer in British film noir studies, film historian William K Everson. We are also dealing with a British screen culture that’s often enjoyed wallowing in another famous notion of British cinema’s non-existence – and the greatest ever put-down of any national cinema: by cinephile/critic/director Francois Truffaut, in 1962, to Alfred Hitchcock – '… Isn’t there a certain incompatibility between the terms “cinema” and Britain… national characteristics… – the subdued way of life, the stolid routine – that are anti-dramatic, in a sense’?

Perhaps Truffaut’s boiling scold is a starting point. Perhaps a reminder also of facts of which Truffaut seemed almost in willful denial: that his Hitchcock was both British and a film noir specialist. It’s not that British cinema doesn’t exist. It’s rather that it’s just a bit like one of those snotty juvenile delinquents that often inhabit its film noirs: grievously misunderstood, by a lack of inquiry into its sociology, a lack of sympathy for its difficult upbringing and its long-standing difficulty in making friends.

British cinema noir is important because it is the best place to start, if you do plan on revising pre-conceived opinions about the nature of British cinema’s existence. Not just because film noir is so often a good place to start (anywhere, in any national cinema), as the genre where you’re always most likely to find the veiled symbols of social criticism, or the most rapidly responsive pop cinema style. It’s also because, at least after 1945, British cinema’s own film noir cycle is the best place to go see the smouldering social revolt against – and precisely, grimly, concerned with – everything Truffaut complained about: Britain’s 'anti-dramatic’ emotional culture. The British 'subdued way of life’. The British 'stolid routine’.

The revisionist project to rediscover British film noir is a comparatively recent one; ironically often led by US critics uneasy that two of their favourite directors – Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Powell – could really have been the only exceptions to the rule of British cinema’s middlebrow-ness. So it can put hard-to-grasp demands on received film history wisdom.

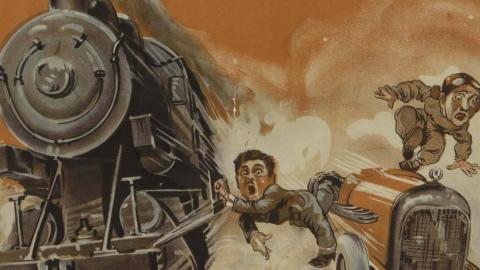

For starters, British noir is rude and raw. As academic Robert Murphy reminds us, British film noir was born in 'the brutal traditions of British popular entertainment – bear-baiting, prize-fighting, public execution…’ There is more class, more spite between classes and more kitchen sinks (even then) than even in US film noir. That aforementioned smouldering resentment sometimes turns into real acid throwing. More razors are pushed into faces than Jimmy Cagney / Public Enemy-style grapefruits. The occasional gun is a real fear-symbol. And firing it becomes a profound social and existential incident.

British noir is also a menace to the canon of British cinema. If it’s not careful, it could take an eye out – the ‘eye’ and heart of Britain’s supposed ‘quality’ cinema. Working through the filmographies of some of British noir’s ‘Subjects for Further Research’ (to borrow American film critic Andrew Sarris’ turn of phrase for underappreciated directors) suggests so many great little films. By comparison, they make some UK cinema ‘masterpieces’ seem like rubbish. Are there some terrible mistakes of value judgement that need to be corrected? Or has there been a real streak of self-loathing in British cinema’s self-judgement?

Standard noir tropes also don’t always make sense in British noir (...vive la difference, Francois). French cinema of the 1930s is a far greater influence than German Expressionism. Femme fatales are almost irrelevant; they are sad or are killed and the neurotic males can destroy themselves without their help. Art direction needs as much attention as cinematographer’s chiaroscuro; Britain’s endless youth sub-cultures and their ‘revolt through style’ is often elaborated here, in on-screen costume and décor. Political telegramming is more overt than in American noir – but implicit in style and subtext, not at the cost of reducing noir to ‘the trimmings’. Indeed, the fates of Timothy Evans, Derek Bentley and Ruth Ellis – and others executed by miscarriages of the 20th century UK criminal justice system – give so much of British film noir its deep, tragic timbre.

What else British noir is can be the subject of your own further research into a national cinema so many have long loved to hate. We do have to acknowledge this selection’s limitations – sometimes the result of an over-abundance of choice. We haven’t begun to unpack all the sub-cycles and variations. We haven’t pursued 1930s pre-war antecedents or the post-1960s neo-noir, glam-gangster films (Get Carter, Stormy Monday, Sexy Beast). We can’t cover all the key directors (Lance Comfort, Roy Ward Baker and Seth Holt are at least three key stylists who are absent). We only name check most; sometimes due to problems getting good prints. We acknowledge but don’t always do the (bleedin’) obvious; Brighton Rock is here, but not The Third Man. And the darker crafts of 60-minute British B-noirs (from studios like Butchers and Anglo-Amalgamated) are barely going to be tapped.

You will notice one bias: towards the expat Australians who so often passed through British film noir. The actors who (curiously, in light of our ‘convict origins’) more often found work as coppers than as crims. Or our first internationally acclaimed cinematographer, Robert Krasner. Or John McCallum and Googie Withers; honoured here with a new print of their most famous collaboration with director Robert Hamer, on It Always Rains on a Sunday. Or others who, like Withers or like actor Michael Craig, became Australian by adoption and played their part in our film production revival. We also note that the end of one of the great brands of British film noir – Ealing Studios – provided Australian cinema with one of its more underrated films, perhaps the one genuine example of Oz-noir: Harry Watt’s 1959 ‘desperate men’ film The Siege of Pinchgut, shot around Sydney Harbour.

If you get the chance, as part of your research we also suggest you see Ken Loach’s forthcoming documentary The Spirit of ’45. It’s an examination of just what the British public hoped for at the same time as the British film noir cycle was emerging. And it’s about how their hearts were broken and aspiration dampened as the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s progressed. This is very much a theme shared by many of the features in the season.

And please come early to sessions in both Canberra and Sydney. Not to avoid having to climb over smoking men in damp trench coats or ladies in big hats (as you would if it was 1945), but to experience our pre-feature selection of what we call 'British noir shorts’: documentaries that give a social history context to the fever nightmares of the features. This will be a chance to discover some of the more ‘noir’ achievements of postwar British documentary and sponsored films. Titles like Alain Tanner and Claude Goretta’s Nice Time (1957) and Michael Grigsby’s Tomorrow’s Saturday (1962) are classics of Britain’s famous ‘free cinema’ movement.

However this selection will also introduce the work of lesser-known UK documentary masters, like Anthony Simmons and John Krish. We will also screen some oddities of the British sponsored documentary, like 1949’s The People at No. 19 – a film about sexually transmitted disease, but in the words of film historian and curator Katy McGahan, one '… closer to contemporary Gainsborough melodramas than to other, more sober, state-sponsored health warnings of the time’. And we will introduce you to the work of Richard Massingham – the Alfred Hitchcock-like genius maker and star of some of the greatest UK sponsored documentaries of the 1940s and ‘50s.

The British film noir season will be presented in collaboration with the Sydney International Film Festival, with special thanks to BFI Distribution and the BFI National Archive. It will screen as part of the SIFF program June 5–16, then at Arc cinema in Canberra from 22 June.

For further background to many of the films and filmmakers showcased in this season, go to the British Film Institute’s screenonline website.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.