BY STEVE CLARK, TREVOR CARTER AND BRUCE COWELL, EDITED BY PAM CARTER

BY STEVE CLARK, TREVOR CARTER AND BRUCE COWELL, EDITED BY PAM CARTER

This is the first in a three-part series. Read Part Two and Part Three.

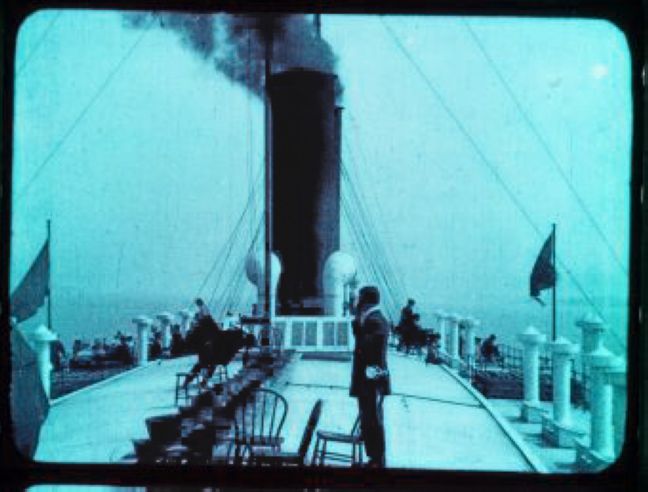

The NFSA’s collection includes early coloured films, many of which are tinted. As these films deteriorate with age, their colours are lost.

Steve Clark, Trevor Carter and Bruce Cowell from the NFSA’s Motion Picture Laboratory share their research about using traditional dyes and techniques to restore tinted films.

Colour film, as we know it today, is shot on colour film stock (sometimes referred to as natural colour).1 However, from the very beginning of the motion picture industry in the 1890s, filmmakers began experimenting with ways to add colour to film by hand painting, stencilling, tinting, and toning their movies. This material became known collectively as coloured film. The NFSA has coloured films (produced in Australia and overseas) and some spectacular examples can be found in our Corrick Collection - a series of nitrate-based films exhibited by a family of travelling entertainers who toured Australasia, South-East Asia and Europe between 1897 and 1914.

We have copied these films to polyester-based black-and-white film, a stable medium, which has allowed us to preserve the content of the films. However, the aesthetic of the films — their coloured light — has rarely been captured.

The NFSA has created cinema print copies of some coloured films using modern colour print stock but the colours are not as authentic as the original tinted film. There are also a number of preservation issues with copying onto colour film that will be discussed later. Drawing on early film manuals and past research, members of the NFSA’s Motion Picture Laboratory have been using traditional dyes to tint black-and-white film.2 These ongoing experiments have produced luminous colours and developed our understanding of the techniques used by filmmakers over 100 years ago.

The invention of motion pictures in the late 1890s followed great advances in industrial chemistry. In the mid-19th century, the first commercially produced synthetic aniline dyes (originally created from coal) revolutionised the clothing industry. In the past, organically dyed cloth was expensive to produce. Because of the cost of organic dyes, many colours were reserved for the rich. With the introduction of aniline dyes, an explosion of colour began taking place on city streets, allowing people from all walks of life to dress in their colourful best. These cheap dyes were also to have a revolutionary effect on the infant motion picture industry.

Unlike most organic dyes, aniline dyes are translucent. In the 1890s, film production companies were starting up around the world, making movies to show themselves or sell to other exhibitors. These early silent films were created using black and white Cellulose nitrate film. Looking for an edge, film companies soon began to experiment with aniline dyes to produce coloured effects. A number of techniques were used to colour film, from hand painting and stencilling to tinting and toning. Some filmmakers used a combination of two or more of these techniques in the same film.

The first coloured films were painted by hand. A group of people (sometimes 40 or more working on one film) would painstakingly paint part of each frame of film. Film frame rates were not yet standardised and different filmmakers made their films at speeds ranging between 12 frames and 20 frames per second. To colour one minute of film for a film running at 16 frames per second production staff had to hand paint 960 frames. Not surprisingly, the process was soon industrialised by using stencils. The major advantage of stencilling (from a commercial point of view) was that it could create more films in a shorter amount of time. However, it was still a time-intensive process.

Stencilled effects range from single colours (highlighting part of the image) to complex multi-coloured scenes. A complete copy of the film had to be created for each colour added to the final cinema print. The area where the colour would be applied was cut out of each frame of the stencil. The stencil was placed over the cinema print and the dye applied using rollers. This process was repeated for every colour. The French company Pathé Frères perfected the technique, applying up to nine colours for each frame of film.3

Toning was invented in the 1880s to colour photographic prints and it was a natural progression for filmmakers to take up the technique. As with stencilling, the first step in toning is to produce a black-and-white film from negative stock. A black-and-white image is made up of microscopic particles of silver, suspended in an [g[Emulsion]]. Silver is neutral in colour, allowing light to be projected through it. In toning a chemical bath removes the metallic silver. The silver is replaced by a metallic salt, which creates a coloured tone.

The most widely known tone is the red-brown colour known as sepia. Sepia is created by replacing the metallic silver with silver sulphide ferrocyanide. Used extensively for colouring photographs, sepia is almost synonymous with historic prints. It is interesting to note that one of the effects of replacing metallic silver with silver sulphide is that it doesn’t decay as fast as metallic silver, which tends to oxidise over time. This means that sepia-toned film generally has a greater archival life than black-and-white film.

Sadly, this was not the case for all toned films: many tones decayed rapidly reducing the life of the film. Ferrocyanide (the iron tone used for producing a blue image), decays quite quickly, changing from blue to murky yellow. Eventually, the decay becomes so complete that it is difficult to tell what colour the original was meant to be.

A number of other toning techniques were used in coloured films, including: mordant dye toning (using basic synthetic dyes); double toning (using a metallic tone followed by a second metal or mordant tone bath); and double effects (a combination of toning and tinting).4 While a full exploration of toning is outside the scope of this document, the NFSA hopes to experiment with toning techniques in the future.

A large proportion of the coloured films in the NFSA’s collection are tinted and this was part of the reason why we concentrated our research on this technique. The difference between tinted and toned film is that toning only affects the silver image, while tinting produces an overall colour cast. In tinting, the entire film base is coloured (including its perforated edge). When a tinted film is projected the image looks like a dark image on a coloured background.5

While tinting and toning were used thoughout the silent film era, tinting was used more frequently. This may have been due to the fact that toning required several chemical baths, making laboratory costs more expensive for toned film.6 Whatever the reason, tinting became so popular that by 1920 the Society of Motion Picture Engineers estimated tinting was used in 80 to 90 per cent of all films made.7

Like toning, tinting was used for physical effects (blue for night scenes, red for fire and explosions, etc). Colour was also used to imply emotional content; for example, pink or lavender for romantic scenes. While it is doubtful that there were any set conventions, there is evidence that directors were aware of the psychology of colour and used it to set the mood in their films.

To induce certain moods, I have scientifically played upon varying degrees of happiness and sorrow with varying shades of pink and green. The heights of joy are enhanced with a delicate pink glow, while the depths of grief call for a ghastly green…’

Producing a tinted film was (and still is) a complex process. Black-and-white cinema positive prints were produced for each copy of the film and the films cut up into the scenes that required dyeing.8 Each roll of film was wound onto a rack (similar to the racks used for film processing), before immersing the film in a large metal vat of dye. To avoid uneven dyeing, it was important that the lengths of film being dyed did not touch during the process. It was difficult to dye film consistently. Uneven dyeing could occur depending on which part of the rack the section of film was wound onto, how long the film spent in the dye, and the concentration of the solution.9 There was always some colour variation between copies of the film. After dyeing, the rolls were cut back into individual scenes and the film joined back together in the proper order to create a cinema release print ready for projection.

Production companies mixed their own dyes (using formulas developed by in-house laboratories) and the recipes for producing these colours were very diverse. In the 1920s, film publications listed over 100 types of aniline dyes.10 As tinting became more widely used, a palette of colours was developed and film manufacturers began to sell pre-dyed film stock. Pre-tinted film gave producers a cheaper and more consistent method for creating coloured cinema prints. It was sold from as early as 1915 to around 1930 and might have been expected to replace the post-tinting process. However, laboratory manuals from the time show that production companies were still using their own tinted films in-house as late as 1927.11

The preservation of coloured nitrate film presents a number of physical and technical challenges. The chemical composition of early cellulose nitrate film means that it burns easily, is extremely difficult to extinguish, and gives off highly toxic smoke.12 In fact, one of the original uses of cellulose nitrate was as an explosive known as gun cotton. Because of its volatility, the use and handling of cellulose nitrate film is governed by strict occupational health and safety regulations and only a limited number of places (film archives and specialist film restoration companies) are able to receive and work with this material. Some of the original dyes can also be flammable, highly toxic, or potentially explosive (Sir William Henry Perkin, the inventor of the first coal-based aniline dye, Mauveine, blew up two factories).13 Apart from the difficulties in handling nitrate safely (without causing damage to the film or the film technician), there are a number of factors that make it difficult to create an accurate copy of a film’s coloured image.

The production of nitrate film stopped in the early 1950s, meaning that the nitrate-based material held at the NFSA is at least 60 years old and some of our films are over 100 years old. As nitrate ages it shrinks and buckles, becomes brittle, and chemically decays. Sadly, this decay cannot be stopped, though it can be slowed with appropriate storage conditions.

Making a new copy is the only way to ensure the future survival of the content of the material. However, as nitrate decays, the film’s colour fades and may even change hue completely over time (making it extremely difficult to tell what the original colour might have been). The type of dye or toner used to colour the image may increase its rate of decomposition.

Worse still, the colour may not decay evenly across the film and this produces a mottled look. This mottling is reproduced in any copies made of the film and is extremely difficult to remove.

Tinting and toning were applied as the last part of the process (to the cinema release print) and the surviving films have usually been projected multiple times. This means that the films have also suffered physical damage such as broken perforations, scratches and breaks. Due to its fragility, nitrate material can only be copied using specialised film equipment that has been modified to deal with problems like film shrinkage.

The NFSA has made black-and-white copies of coloured films (keeping a written record of the colours used in the original). While not ideal, this method allows us to keep the film’s content (its information) in a format that has a long archival life. Coloured films can also be reproduced by printing a copy on modern colour polyester film or by using the Desmet system (explained below). While both these methods have benefits, they also have a number of issues from an archival point of view. Colour film stock is expensive and may fade over time. Another issue with using colour film is inaccuracy in reproducing tinted and toned colours. Some of the colours produced by the original tinting and toning techniques fall outside the range of colours available in modern duplicating film stocks. Camera stock (film used to shoot movies) is designed to capture a wider range of colours and can be used to compensate for this issue. However, camera stock is not as fine grained as duplicating stock and this can result in a loss of image resolution. Coupled with this, there is frequently an issue with the condition of the original film. Many nitrate films have already faded. With this in mind, questions must be asked. What are we trying to capture? How true will the representation be if all we are copying is a faded image?

The Desmet colour method is another photomechanical process, used to reproduce tinted or toned films. Developed by Nöel Desmet from the Royal Belgian Film Archive (Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique), this technique involves producing a black-and-white negative of the original, which is copied as a positive (neutral grey) image onto colour print stock. Coloured tints or tones can then be replicated by exposing the colour print stock using a combination of red, green and blue filters on a Continuous printer. The printer’s light settings are chosen to replicate the colour of the tint or tone required.

Colours can be simulated by placing the black-and-white negative between the light source and the colour print stock. For example, to create a red tint the negative would be placed between the light source and colour print stock and the filters set at Red 14, Green 14, and Blue 14. Some colours can be replicated by pre-flashing the raw stock without placing the negative between the light source and the colour print stock. To create a red tint using pre-flashing, the colour print stock would be pre-flashed at a green filter light setting of 40 and a blue filter setting of 50.

The Desmet method provides a convincing visual illusion and allows greater range of colours than copying straight to colour film stock. It also makes contrast control easier. However, because Desmet uses modern colour film stock, it cannot entirely reproduce the saturation and hues of the original tinted films and colour copies deteriorate more quickly than black-and-white film.14 Another issue is that only a few film restoration companies specialise in this technique. The expense of using an external provider, and the risk of physical damage or loss involved when the films travel for restoration, means that this technique has only been used for a small number of coloured films in the NFSA’s collection.

As Desmet produces single hues it cannot be used to reproduce multi-coloured stencilled material. Stencilled films can currently be copied only by using photomechanical reproduction, using either black-and-white or colour film. As mentioned, modern colour film does not have the ability to accurately capture the colours in the original. Added to this, if the colour in the original has faded, the copy can only reproduce the faded colour.

The original film can be scanned to produce a Digital intermediate (DI) and the results digitally enhanced. Film scanners only capture a limited type and number of colours as they are designed to copy film. However, once a digital copy is made it can be enhanced to include a wider range of colours and many physical defects (such as scratching) can be removed. The digital copy can then be printed back to modern (natural) colour film or viewed electronically (on computer monitors or in digital cinemas).

Currently, the NFSA can only reproduce stencilled material as black-and-white copies in-house. For colour copies, the originals must be sent to a specialist film restoration company. As with the Desmet method (described above), the cost of doing this, and risk of damage to the film during transportation, means that digital restoration is used for only a limited number of films in the collection.

This is the first in a three-part series. Read Part Two and Part Three.

1Paul Read and Mark-Paul Meyer, 2000, Restoration of Motion Picture Film, Butterworth-Heinemann, p180

2Motion Picture and Film Archive Consultant Brian R Pritchard has reproductions of Kodak tinting and toning manuals from the 1920s on his website, published on-line at http://www.brianpritchard.com/Tinting.htm

3Read and Meyer, p41

4Carl Louis Gregory,1928, Motion Picture Photography (second edition), Faulk Publishing Co. Inc., see Chapter 11, published on-line at http://www.brianpritchard.com/Tinting.htm

5Read and Meyer, p182

6Richard Koszarski, 1991, An Evening’s Entertainment: the Age of the Silent Feature Picture, Charles Scribner’s Sons, p127; Read and Meyer, p185

7Koszarski, p127

8Read and Meyer, p274

9Read and Meyer, p185

10Read and Meyer, p182

11Read and Meyer, p184, p274

12United Kingdom Government: (date unknown), ‘The dangers of cellulose nitrate film’, pamphlet published online at http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/cellulose.pdf

13Read and Meyer, pp. 272–273; Wikipedia, ‘William Henry Perkin’, accessed November 2011 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Henry_Perkin

14Read and Meyer, p290

The title for this work was inspired by the Dylan Thomas poem ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’, Dylan Thomas, Collected Poems 1934–1952.

Main photo: Tinted image from 'Voleurs de Bijoux Mystifies’ (Pathé Frères, c1910) NFSA: 746460

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.