Everything’s Connected

By way of introduction, let me establish my lack of credentials for writing a piece concerned with the interplay between reality, literary pursuits, radio broadcasts, and late 20th century electronic music. My work for the NFSA is centred around tending to the needs of a database and its users rather than saving an obsolete format from oblivion in the nick of time or discovering rare gems in the national audiovisual collection and showing them to the world.

I am, however, a word nerd of the first order. This can be a curse or blessing for those around me (depending on their reaction to impromptu explanations of gerunds and use of the case system for English pronouns). Being a word nerd also means that when I am listening to songs it’s the lyrics, more often than not, that are to the forefront rather than the rhythm and melody. I sometimes wonder if I decided that I liked The Clash just because they correctly used ‘whom’ in ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go?’ (1982).

So how did a flat white lead to a murder?

After a general staff meeting, I wandered through the exhibition Great Adaptations: Words to Image on my way to the café in search of coffee. As I checked out the posters from Australian films and compared the text of the original works with the screenplays, my mind wandered from great to not-so-great translations of books to screen (why is it so hard to get a John Irving novel to work on film, for instance?) then to thinking about songs I knew that had literary antecedents. Skipping the more obvious candidates (Kate Bush’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ and Led Zeppelin’s ‘The Battle of Evermore’), the first five songs that came to mind were: ‘Killing an Arab’ by The Cure (Albert Camus – The Stranger), Nirvana’s ‘Scentless Apprentice’ (Patrick Sűskind – Perfume: The Story of a Murderer), ‘Shadows and Tall Trees’ by U2 (William Golding – Lord of the Flies), ’2+2=5’ by Radiohead (George Orwell – 1984) and the Crash Test Dummies’ ‘Afternoons and Coffee Spoons’ (TS Eliot – The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock). Another line from Eliot’s poem served as the title for Patricia Rozema’s 1987 film I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing.

Leaving aside what this list says about my taste in music, I noted that I could call up more songs based on novels than on poems which seemed counterintuititive. Perhaps poetry’s similarity to song lyrics makes it more difficult to adapt than prose. Thinking about it a little more, I could dredge up a couple of instances of artists setting poems to music: ‘The Stolen Child’ by The Waterboys (WB Yeats) and ‘Puedo Escribir’ by Sixpence None the Richer (Pablo Neruda). With no further research on the matter, I decided that poems were more often than not too short in their narrative structure to be repurposed to another format.

The other thing that struck me about my list was the bleak subject matter. Was my taste in music morbid or did this tendency hold true more broadly? I resolved to do a little research on the subject.

It’s not me.

A quick review of the various lists on the internet (ahem) shows that most songs from literary works are concerned with the darker side of humanity (Vladimir Nabokov, Mikhail Bulgakov, Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville) and fantastic (JRR Tolkein), folkloric (Greek myths, usually the bloody bits) or terrifying (Stephen King, Bram Stoker) themes.

_______________________________________________

And another thing …

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita is credited as an influence on Mick Jagger during the writing of ‘Sympathy for the Devil’. It has multiple film connections too, including: Swiss artist HR Giger (creator of some of the best creepy goodness in the Alien franchise) naming a 1976 painting after Bulgakov’s novel … and that painting ending up as the cover art for Danzig’s 1992 album How the Gods Kill.

_______________________________________________

Following the bleak subject idea, I remembered the track ‘Dead Eyes Opened’ by Severed Heads from the mid 1990s (itself an adaptation of a 1983 single). This was the first electronic music I remember listening to without thinking, ‘Why?’. Given my leaning towards the lexical, it will come as no surprise that I wasn’t much taken by modern ‘dancey electronic stuff’ – a term I used for any music that had less than three or four verses (with different words in each). A note to music boffins: feel free to roll your eyes at the screen right now.

For those unfamiliar with ‘Dead Eyes Opened’ (1994), it’s available to listen to here. The track starts with the mellifluous tones of Edgar Lustgarten reading from his work ‘Death on the Crumbles’. Lustgarten (1907-1978) worked with the BBC (in both radio and television) rendering adaptations of his written works about the desperate, dodgy and devilish miscreants of the criminal world. His shows were highly successful throughout Britain, America and Australia in the 1950s and 1960s.

It was Lustgarten’s spoken word element of the track that got me listening. Both the voice and the subject matter were arresting – opening a song with the line: ‘I’m not going into details, it’s too horrible …’ is genius. The spoken word element of the song also refers to Sir Bernard Spilsbury (of forensic science fame) and Edgar Wallace – who brings this piece full circle.

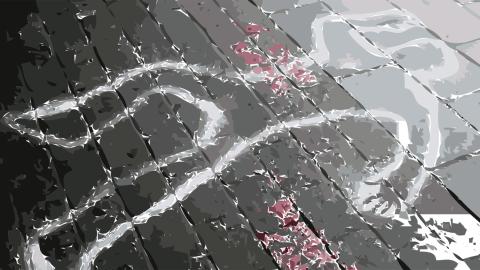

We’ll deal with the gruesome before heading Wallace-ward, the ‘too horrible’ tale is as follows. On 15 April 1924, Patrick Herbert Mahon murdered his pregnant lover, Emily Beilby Kaye, in a rented bungalow at Eastbourne, Sussex, UK. After the murder, Mahon dismembered Emily Kaye’s body and tried to dispose of it using various methods it’s probably best not to go into here. (Those of you with staunch stomachs can find out more by following the links below.) Even more disturbingly, he brought another woman to the bungalow for a clandestine nighttime adventure even though Emily Kaye’s remains were still in one of the bedrooms. He was arrested on 2 May 1924, tried and found guilty at Sussex Assizes, and executed at Wandsworth Prison on 2 September 1924.

Edgar Wallace was born in London in 1875 and died in Beverly Hills in 1932. He was a prolific author of, among other things, novels, screenplays, and true crime writing. In 1928 the transcript of the Mahon trial was published with an introduction by Edgar Wallace – to which Lustgarten makes reference in the spoken word element of ‘Dead Eyes Opened’.

Edgar Wallace is probably most famous these days as the co-creator (with Draycott Dell) of King Kong – both the short story, and the early screenplay and story for the film based upon it. There are, in fact, over 160 films adapted from his literary works.

And thus the circle is complete and everything is connected – from a craving for coffee to an exhibition about film adaptations of literary works followed by a meander through literature in modern music, on to a particular track from the mid 1990s that referenced a murder in the 1920s which was related to one of the most adapted modern authors in film history.

Finally, I can only think of two novels that take their titles from songs, both by Douglas Coupland: Girlfriend in a Coma and Eleanor Rigby. Are there more out there that you know of?

_______________________________________________

Also …

Edgar Lustgarten was parodied as ‘The Criminologist’ in the 1975 film The Rocky Horror Picture Show … which was based on a 1973 musical stageplay, The Rocky Horror Show.

_______________________________________________

References

Edgar Wallace – The Official Site

Legends of True Crime Reporting: Edgar Lustgarten

See Rocky Music Org for reference to Lustgarten and The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

‘Bungalow Murder’ (The Argus, 13 September 1924)

The Trial of Patrick Mahon (Dilnot, George, ed., Introduction by Edgar Wallace, Geoffrey Bles, London, 1928)

Patrick Herbert Mahon on Murderpedia

See Douglas Cruickshank’s ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ on Salon for a discussion of the song and its link to Bulgakov.

All images used are in the public domain.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.