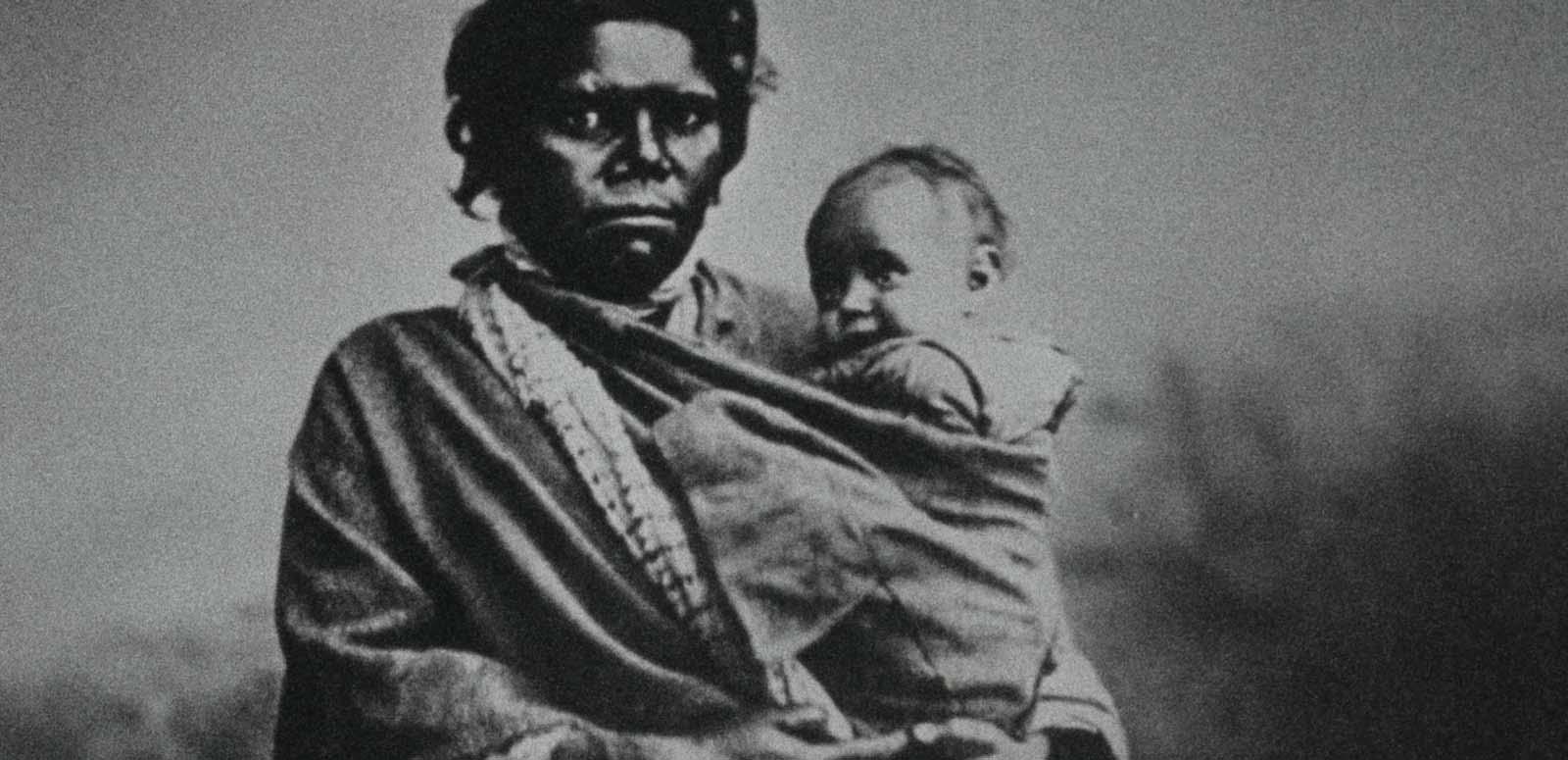

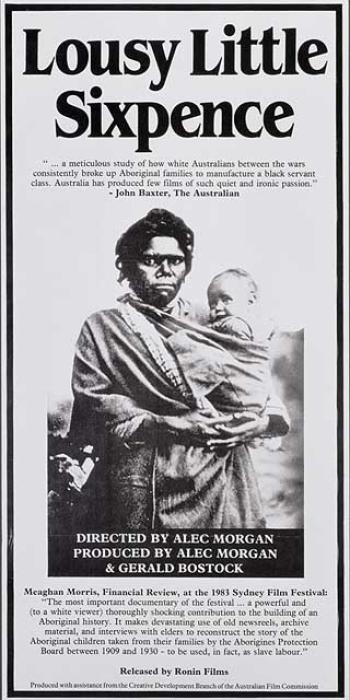

The NFSA has completed a digital restoration of the groundbreaking documentary Lousy Little Sixpence (1983). Ruby Arrowsmith-Todd talks with director Alec Morgan.

WARNING: this article contains names, images or voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.