NFSA Historian Graham Shirley recalls the restoration of For the Term of His Natural Life (1927).

NFSA Historian Graham Shirley recalls the restoration of For the Term of His Natural Life (1927).

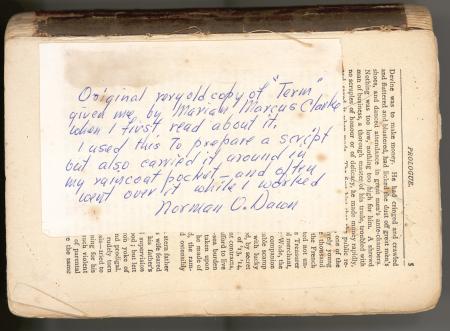

In 1926, an actor called Marion Marcus Clarke gave an early edition of the classic Australian novel For the Term of His Natural Life to American director Norman Dawn, who was about to make Australia’s third film adaptation of the book. Marion Marcus Clarke, besides playing mother to the hero of this film, was a daughter of the author of For the Term of His Natural Life, Marcus Clarke (1846-1881).

In July 1970, Norman Dawn wrote to me that during the filming of For the Term of His Natural Life he had used this copy of the novel ‘to prepare a script but also carried it around in my raincoat pocket — and often went over it while I worked’. This copy, when Dawn posted it to me from Santa Monica, California, to Sydney, Australia, in 1970, was annotated throughout with pencil notes Dawn had made before and during the making of his film. Lines of dialogue were underlined, passages emphasised with marks and margin comments, and entire pages of what Dawn considered superfluous action were crossed out. Eleven years later, I was to use this copy of the novel to restore Dawn’s For the Term of His Natural Life.

The story of this restoration goes back to 1970, when I was working temporarily in television in Canberra on evening shifts, and had three weeks of mornings to spare. Wanting to learn about Australian film history at a time when there was very little published on the subject, I phoned the Canberra-based National Library of Australia (NLA), where I had read there was a film archive holding what survived of early Australian cinema.

‘What survived’ turned out to be the operative term. Where I had phoned expecting to be able to view any Australian silent film I wanted, the person I had reached — Ray Edmondson, who at that time virtually was the NLA’s National Film Archive (NFA) — patiently explained that less than ten per cent of Australia’s silent film output survived, and that a number of those that did survive, remained only as fragments.

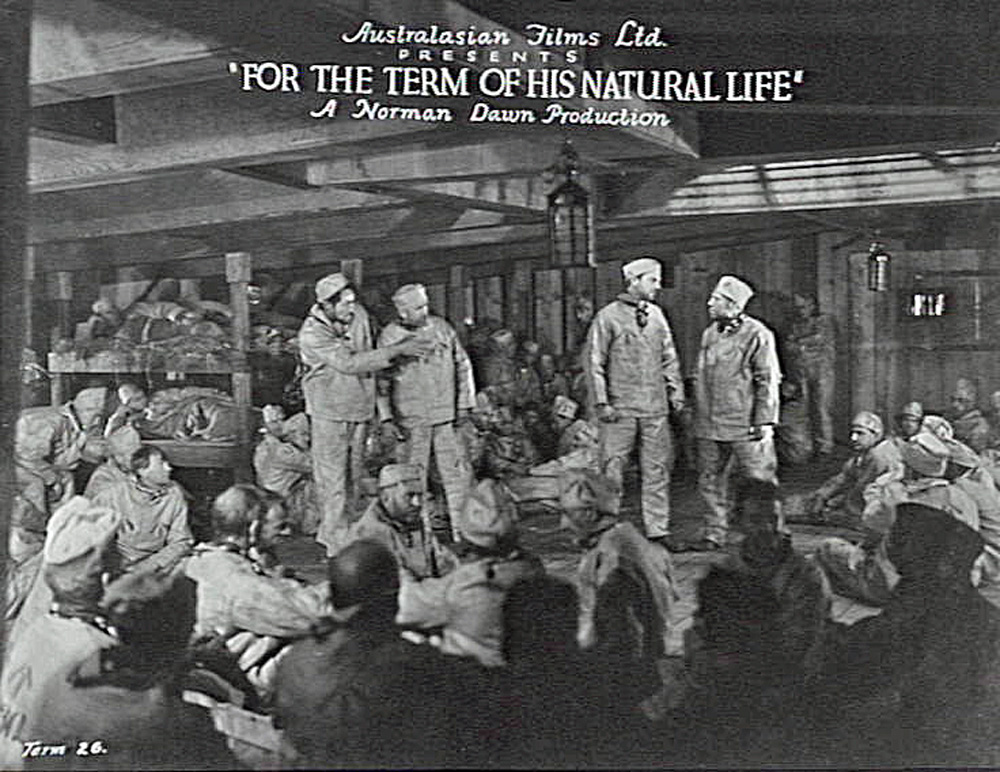

The fact that a young person was asking about early Australian cinema intrigued Ray enough to invite me to visit the NLA to view a selection of the remnants of Australia’s silent and early sound eras. What I viewed — run on 16mm in the NFA’s theatrette — was a tantalising cross-section of the survivors, fragments as well as complete films. Out of the fragments, I was bowled over by the epic sweep, visual innovation and atmosphere suggested by the often truncated and deteriorated moments of the 1927 For the Term of His Natural Life (Term).

By the end of these screenings, I wanted to learn what I could about Norman Dawn, a pioneer of most of the special effects he had used impressively throughout Term. Ray encouraged me to write to Dawn, and on writing to him I received an immediate reply. His son had just died of a stroke, and he was glad of the chance to exchange letters on matters far removed from his family crisis. From these first letters, a five-year pen-friendship developed, with Dawn sending me memories of his time in Australia and his career generally, and me reciprocating with questions and news of an Australian feature industry that was at that time just starting to revive. The friendship, which included my visiting the US to interview Dawn in 1972, was only stilled by his death in 1975.

An incomplete nitrate print of Term had been sent to the NFA in the 1960s, with the missing sections having fallen prey to vault flooding and nitrate stock decomposition. But in the late 1970s, the American Film Institute had responded to the NFA’s efforts to track down missing Australian features overseas by sending the NFSA a momentous rediscovery – the US release version of a longer although still incomplete nitrate print of Term. News of this rediscovery became public in June 1980.

Since I had by this time worked as a film editor and was well versed in Dawn’s Australian work, Ray Edmondson invited me to editorially restore For the Term of His Natural Life. In March 1981, I started work on the restoration. I spent an initial few weeks in Canberra viewing all available materials (including stills for scenes that remained missing), and working out a reconstruction script. As I viewed and took notes from the Australian and US versions, I discovered the US version consisted almost entirely of variant takes and out-takes. Not only were takes used in the US version usually of a lesser performance quality (for instance, lead actress Eva Novak is seen to giggle in one supposedly very serious scene), but the storyline had been condensed and rearranged. Some of the scenes had become fragmented through wear and decomposition, while other scenes, especially those indicated by surviving stills, were completely missing. The US version also had different intertitles that used a more abbreviated, punchier writing style.

In the absence of a script, a synopsis or even censorship records for the film, sorting out the Australian original’s storyline was a distinct challenge. Dawn’s copy of the Term novel was of great help, as was the surviving Australian version of the film (more faithful to the novel than the US version), an unused script by Victor Longford and Dorothy Gordon, a microfilm of Norman Dawn’s scrapbook, publicity about how the film was made, and information on the film’s content in my correspondence and my interview with Dawn. Surviving documentation for the film included an extensive press sheet with a music synopsis that provided further information on what sequences followed which. Once I had worked out the structure, it took me three days to assemble the 35mm work print that had been printed for the reconstruction. My remaining time until the restoration’s premiere was a constant process of editorial finetuning and the addition of newly-filmed stills, optical shots, intertitles, and planning for scoring and colouring. While some of the reels were no more than two edits and a wind-through, others (for instance, the restoration’s 35mm reel 5, which came mostly from the US print), had more complicated demands.

The restoration was originally planned to be a black-and-white silent. Ray Edmondson, however, impressed by the potential of what was emerging as the Term reconstruction started to take shape, approached the Australian Film Commission (AFC) for funding that would now enable the restoration to replicate silent-era colour tinting and toning, and the recording of an orchestral score. The AFC — with Director Project Development, John Daniell, being particularly supportive — agreed to part fund the restoration by investing $68,030 on the same basis as if they were financing a new film. From here the project grew in the public imagination as something worthy of the scale of the original production.

Film Australia, based in Sydney’s Lindfield, proved more than generous, offering cutting room space and 35mm editing gear, negative cutting staff and facilities, and their ‘Crystal Palace’ mixing theatre and staff to record the score. Film Australia also assigned one of their staff directors, Graham Chase, to make a documentary on both the restoration and the making of the original film, called Epic. The Graham Chase connection also led to a musician friend Jimmy Stewart (no relation) who, in turn, was a friend of John and Robyn Godfrey, principals in the Sydney-based Palm Court Orchestra, who specialised in re-creations of Edwardian-era music and owned a sizeable vintage sheet music collection called the Benvenuti Orchestra Collection. When I showed John Godfrey Term’s music synopsis, he recognised many of the cues as being stock music pieces that were held in the Benvenuti collection. In addition to the pieces used from this collection, Godfrey and conductor Bransby Byrne adapted other pieces to suit individual sequences.

With emerging documentary filmmaker Michael Cordell working as editing assistant, I drew the reconstruction of For the Term of His Natural Life from the following:

Having found the film’s climactic storm at sea and shipwreck too fast on projection, I took the liberty of ‘stretch-printing’ (the optically printed repetition of frames) to slow it to a natural speed. I also froze or stretch-printed a number of shots otherwise surviving only as several-frame fragments. While such techniques have fallen out of favour in film restoration since the early 1980s, at that time there were few widely circulated precedents to restrict me. I also knew, given that so many images from the original release version were still lost, the restoration I was undertaking already approximated and could not replicate the original.

Ray Edmondson recalls:

'At the time, reconstructions of silent films on such a scale were unusual anywhere and certainly unprecedented in Australia. We had an objective, which was to show Australians a silent film in something approximating its original manner of presentation so it could be enjoyed as a drama, and so we could explode a few myths about silent movies. But we were deliberately not purist about it because we knew we had to make allowances for the expectations of modern audiences if they were to really enjoy it. What was acceptable to a 1920s audience would not necessarily work for a 1980s audience; hence decisions like slowing down the storm sequence to a realistic pace. We also had to accept that when the film went on theatrical release it would be shown in wide screen ratio (1 to 1.85) instead of 1 to 1.33 because cinemas no longer had lenses for standard ratio (fortunately the visual composition of the film meant it could largely tolerate that).'

Most silent-era films had been tinted and toned, with tinted prints made on stock whose base was specially coloured as, for instance, rose pink, sunshine yellow, or midnight blue. An alternative way of colouring films was to run an entire black-and-white print through a coloured dye bath. Toning was a different process in which the black-and-white silver image was reprocessed to produce sepia or other shades instead of black. Complete reels were assembled with various sequences in appropriate tints or tones.

I took creative licence in deciding how and where to colour the restoration. The NLA had, at one point, made a 16mm colour print as a record of the surviving Australian version’s tints and tones, and I was surprised on viewing this to see how conservative the colour choices were. The lab work for the restoration was handled by Sydney’s Colorfilm Laboratories, whose Technical Manager, Dominic Case, had mastered a way on Phillip Noyce’s Newsfront (1978) to combine archival newsreel black-and-white with newly shot colour scenes without the monochrome scenes taking on any unwanted colour bias once both were printed onto colour stock. Since the tinting and toning system used on the original Term and other films of the silent era — colouring individual scenes using special chemical baths — was no longer a possibility, Dominic developed a system in which normal colour positive print stock was pre-exposed to simulate the effect of base tints. Using this stock, Colorfilm lab staff then employed normal colour grading techniques to add assorted colour tones to the black-and-white image. As silent filmmakers had, we used the new tints and tones to literally or symbolically match the settings, actions and emotions: sepia for interiors, blue for night, sunshine yellow for daylight exteriors, dark green for claustrophobic bushland, and red for passionate scenes or fire.

On 5 June 1981, with live accompaniment from the Palm Court Orchestra, the restored For the Term of His Natural Life, running at 97 minutes, premiered on the opening night of the Sydney Film Festival at Sydney’s State Theatre. Among the guests were Jessica Harcourt, who had played the film’s femme fatale Jessica Purfoy, Edward Howell, who had played the young convict, Cranky Brown (and who gamely removed his shirt for a re-enacted ‘lashing’ outside the cinema this winter night), the film’s uncredited co-editor Mona Donaldson, and Bill Carty, one of the film’s brace of cameramen.

The restoration, which had already swamped publicity at that year’s festival, was well received. The Palm Court Orchestra, whose live performance did so much to enhance interaction between film and audience, triggered a standing ovation the moment the film ended. Following the Sydney premiere, the orchestra’s score was recorded for the composite print that was screened on the closing night of the 1981 Melbourne Film Festival.

David Williams, then the managing director of the Greater Union Organisation (GUO), a corporate successor to the Australasian Films that had produced Term, arranged for GUO to donate to the NLA — and hence ultimately the NFSA — the rights that GUO still held in Term. GUO distributed the restoration for its Australian theatrical release, and the restoration went on to have wider international exposure than the film’s original version ever did. It was shown around the world at festivals and conferences, screened on Australia’s ABC-TV and released on video, while its score was sold on LP. Above all else, the Term restoration drew unprecedented public and political attention to the work of Australia’s National Film Archive. This attention helped pave the way for wide acceptance of the federal government’s creation in 1984 of an autonomous National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Main image: Production shot of cast and crew of For the Term of His Natural Life (1927) on a rocky beach. NFSA title: 347553

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.