Reflections on film preservation

I’ve been thinking about film preservation – not unusual for someone working in the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) I suppose – but my thoughts were triggered by a recent comment by NFSA’s Curator Emeritus Ray Edmondson that a particular film had ‘been preserved’.

‘You can’t ever say a film has ‘been preserved’ he said. ‘It’s an ongoing task.’

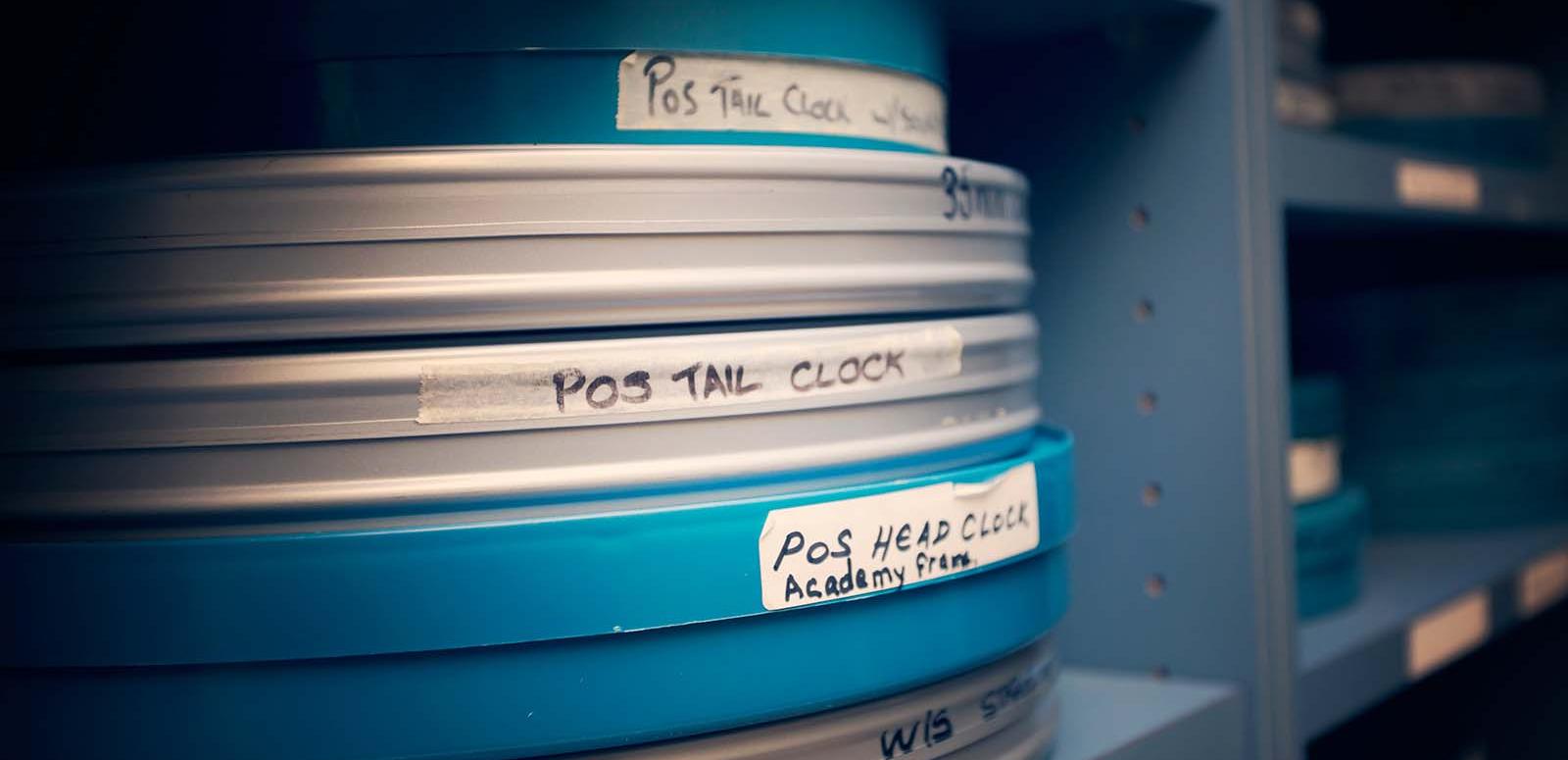

His point is a good one. Acquiring the negative of a film, or making a new, top quality duplicate negative on modern polyester stock is only the start of the task of preservation.

We still have to look after that negative in the correct storage environment, monitor its condition (along with a million other items) and maybe use it on occasion to replace access copies that have become damaged or worn by use. Passive preservation involves looking after the existing material in optimum conditions: active preservation involves copying the original onto newer, longer-lasting materials. In the case of older (and not always so very old) titles, it might turn out one day that a better quality, or more complete version, of the film is discovered, in which case the present archival copy can be superseded by a better one.

So just like the old cliché of painting the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the job of preservation is never-ending.

While we are on the subject, there are several other terms that I hear used, sometimes interchangeably, with the term ‘preservation’. They all mean quite different things and the difference can be very significant.

The NFSA Deluxe Kodak project, for example, makes new prints of five feature film titles from the past 40 or so years, together with remastered sound negatives and new duplicate negatives for preservation. There is sometimes considerable work in identifying the best elements to work from, but apart from more thorough than usual negative cleaning, the job is simply one of re-establishing the right colour grading (working with the original director and cinematographer – sometimes even the original grader) and making new prints. I’d call it just that, ‘reprinting’, in the hierarchy of terms I’m putting together.

Wake in Fright comes from that period, but producing new screening prints of that film involved a lot more than reprinting. The colours on the negative had faded badly and it wasn’t in great condition. The entire film was scanned digitally, cleaned and colour-corrected frame-by-frame, re-recorded back to a 35mm negative and then printed. This is a good example of ‘restoration’ – a whole level up from plain reprinting.

The end product of both these operations is a print that is as close as possible to a new print from the original release. There is no creative change involved, and this is generally a guiding principle for archivists of all sorts.

The same principle ideally applies to the next level up, which is ‘reconstruction’. However, in instances where the complete original negative is no longer available, or where parts are too damaged to use, there has to be some creative interpolation. For example, The Sentimental Bloke (1919) existed in two forms, both imperfect. The complete and original cut of the film was copied to 16mm half a century ago, and consequently was of poor quality with grainy indistinct and poorly-framed images. The original negative was found in the USA, but it had been cut down to a shorter version with American intertitles. The tints and tones of the original prints survived in a tantalisingly small number of single frames, and even those were badly faded. A considerable degree of judgment was needed to put the bits back together, and to create new intertitles where the old ones were cut out and lost. The result may be close to what the original film looked like – in its Australian version – but it is most unlikely to be the same.

Other films have had to have much more interpretive work done to achieve a watchable product. For example, the shrunken and badly decayed fragments of The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) that have survived were extensively repaired, and interspersed with black frames to replace those parts of the reel that were totally disintegrated.

Finally, although it usually falls outside the mandate of an Archive, a number of films have been re-interpreted. New, modern soundtracks for silent films; re-edits to suit a different purpose; or simply replacement of sections previously excised by the director, the production company or the censor.

It’s not always clear cut. First Contact (1983) was at the borderline between reprinting and reconstruction. The film was made originally in 16mm and the NFSA decided to make a 35mm print for theatrical screenings. This was achieved by means of a digital scan, a colour grade, and record out to 35mm film. It was a digital intermediate process, resulting in a new format print, and the few subtitles were recreated: but there were no creative changes and the film wasn’t restored in the sense of a frame-by-frame clean-up.

So that’s it. ‘Reprinting’ is just a clean-up; ‘restoration’ is major repair work on a complete film; ‘reconstruction’ is creating a new, altered work from original components; and ‘preservation’ is the ongoing business of ensuring that the film will be available in years – even centuries – to come.

Dominic Case first became involved in film restoration in 1981. He is the author of Film Technology in Post Production and currently works at the NFSA.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.