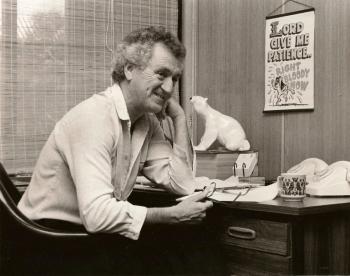

Vale Tom Manefield

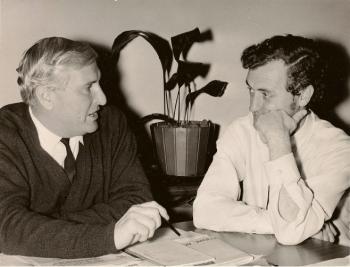

August 15 brought the funeral of Australian television and film documentary producer Tom Manefield (1927-2013), who had died in a street accident in suburban Sydney on 23 May. Among those who delivered eulogies were Manefield’s long-term industry colleague and friend Storry Walton, and researcher- interviewer-director Robin Hughes. With the Chequerboard (1969-1975) Australian Broadcasting Commission documentary series which he initiated, Manefield had pioneered a new style of TV documentary, in the process giving many young filmmakers, Hughes included, vital opportunities that shaped their careers.

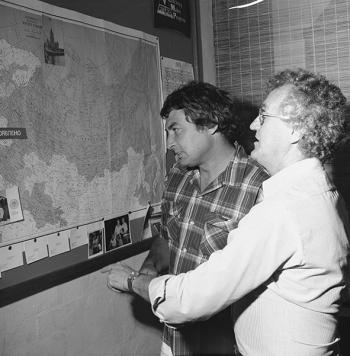

One of Hughes’ Chequerboard contemporaries was David Roberts, who after Manefield started producing for Film Australia, directed for him Walya Ngamardiki (The Land My Mother) (1978), a film about Australian Indigenous connections to land. Other Film Australia projects produced by Manefield included the 10-episode Why Can’t They Be Like We Were? (1976), on adolescent attitudes; the six-part Growing Up (1977), on adolescent sexual attitudes; the 20-part TV series Our Multicultural Society (1979); Chase That Dream (1979), for the Department of Housing and Construction; and the three 90-minute TV documentaries that constituted The Russians (1979).

It was controversy over The Russians that caused Tom Manefield to be dismissed from Film Australia, then to be reinstated after an appeal. When I recorded an oral history with Manefield for the NFSA in August 1990, The Russians remained a sensitive topic. Toward the end of the first of our two recording sessions, Manefield said he wanted to re-read his own records before saying anything about that series. When we re-convened a week later, Manefield was not only fully briefed but filled with a determination to tell his side of the Russians story with the kind of sharp-edged accuracy he had believed in as a producer. He proved to be an excellent interviewee, revealing a detailed recall of people, events, programs and films, and with clever precision nailing the cultures of the ABC and Film Australia as government institutions.

Manefield resigned from Film Australia three months after he had rejoined the organisation following his post- Russians reinstatement. By the time I interviewed him he had been thoroughly enjoying himself driving and owning Sydney taxis for a decade, often ferrying people like me on journeys that were spiced with his smart, witty comments and plenty of laughs.

In their eulogies to him, Storry Walton and Robin Hughes have captured what Walton defined as Tom Manefield’s ‘high voltage’ personality and Hughes has called his total commitment ‘to the idea of challenging established authority’. But they also speak of his fine intellect, his passion for social justice, and his contributions to Australian television and film as an innovator, mentor and agent provocateur.

Storry Walton:

Candour is the quality that comes first and last to mind when I think of Tom.

The little boy of the leafy Sydney suburbs and Queensland bush, with blazing green eyes, entered the world with two luminous and irreparable conditions that set the course of his life. He was born with an over-active bullshit detector and an under-active filter between his brain and his lip.

As a result, by the time he burst into our lives in the late ‘50s he was a man of breathtaking honesty and candour. Disconcertingly outspoken and of high intelligence, volcanic energy and impulsiveness, he suffered neither fools nor dullards gladly. Tom was contemptuous of bad argument and, vexing for his bosses, he was nobody’s lackey. And he had that most precious of showbiz combinations – talent and flair.

I thought of him as an electric man. High voltage. Lit from within. Radiant.

With all this, he had highly developed political and ethical ideals that swung around his concern for justice and his outrage against its antithesis, social injustice. If you believe, as I do, that justice is the highest expression of love, then Tom was imbued with love in its highest degree, even when it expressed itself tempestuously.

This is not a description of an ordinary man. He wasn’t. Dear, impossible, wonderful man, I never met anyone like him.

It was absurd then that the Fates, mischievous as ever, sent this eccentric, passionate, outspoken, anti-authoritarian, free-thinking entomologist to work in – of all places – an ordered, hierarchical, conservative, public service bureaucracy – the Australian Broadcasting Commission. It was not always a good fit, yet this awkward duality worked. While on the one hand Tom rebelled explosively against the dull wits, intellectual lassitude and inertia he encountered in the institution, on the other hand the ABC gave him a secure, well-funded ground in which he could make his often audacious programs – there were people in high places at the ABC who admired and supported him.

I met Tom in 1958 at the ABC. We were soon good friends and colleagues, though I had cause to doubt how deep the bond was when, after he told me that he and Nan were to be married, he asked me if I would be his best man and co-witness.

‘Oh Tom,’ I responded, perhaps a bit too effusively, ‘thank you, thank you so much…’ But he stopped me. ‘That’s okay mate,’ he said. ‘You have lovely handwriting and we thought your signature would look good on the marriage certificate’. We never looked back.

It was a decade and a half of tremendous social change, political activity, and creative vitality. Australia was waking from its wartime severities and the staid 1950s. It was the time of Vietnam War protests, freedom rides for Aboriginal rights, the pill, women’s liberation, sexual experimentation, hippiedom, the Nimbin communes, the Beatles, the Stones, bell-bottoms and flares. And a revived sense of national identity in the creative world was inspiring a tentative re-emergence of an Australian film industry.

The tallest landmark in Sydney was the AWA radio mast, stoic symbol of a passing era. Johnny O’Keefe was rocking around the clock, and the trams still ran down William Street and all the way out to Watson’s Bay via Kings Cross, where, at the Metro Theatre in 1969, 24-year-old Jim Sharman directed the first production in Australia of Hair – with film inserts by Albie Thoms. We were all young and gorgeous and a bit drunk on the exhilaration of the times. I sometimes think that Tom was not so much eccentric as a living expression of the throbbing tumult of the times – albeit out on the extreme edge.

One of his early roles was the Australian researcher and director for the BBC’s landmark Great War series of 1964 under Executive Producer Tony Essex and BBC Researcher Therese Denny. Even with the prestige of the BBC behind the project, the ABC was staggeringly slow to provide an office for him and Therese. When staff arrived at the Brysons Building production offices in Woolloomooloo one Monday morning, the lift doors opened to reveal a desk with Tom seated behind it, studiously at work and using the lift phone. In protest at the delays, he had commandeered it as the Great War office, and he stayed there, going up and down, until a stationary office was found.

The Great War aside, Tom was, like all of us, initially one of the ABC’s Production Pool, a kind of primordial pond, from which, amoeba-like, we were scooped up every fortnight by the program boss to be allocated to any and all types of live-to-air programs.

One effect of this ponding of producers – an apt collective noun – was that people from the whole gamut of ABC production disciplines and departments met and shared ideas. The venue was the Gladstone Hotel in William Street – the Gladdy – and here Tom was in his element with colleagues from News, Rural, Education, Children’s programs, Drama, Talks, Light Entertainment and Sport – the place was always furious with argument on politics, television programs, the social order and football – Tom in the middle of it, often sparring with his scholarly friend, John Croyston – Tom incandescent with enthusiasm or indignation, and always punctuating the air with his characteristic mannerism – the Manefield Stab, the fist tight, the third finger ramrod straight. He was at home in that eclectic bibulous milieu.

When, from the Pool, Tom was allocated the production and direction of Womens’ World, he found an intellectual match in its presenter Mary Rossi. They stood the program on its head. They turned it from home-making, fashion and lamingtons to current affairs, social issues and lamingtons. When the sale and promotion of margarine was being resisted by the dairy industry and the powerful Country Party influenced the ABC to restrict the use or mention of it (in favour of good cow-uddery butter), Tom and Mary defied the ban. Not too subtly either. Whenever a recipe called for margarine, Mary would say to camera, in exaggerated invisible inverted commas ‘now take two ounces of that well-known substitute for butter ’. Tom sang the phrase at the pub as a slogan of political defiance.

Controversy clung to Tom’s ankles. As Executive Producer, he engaged me as national producer/director of one of the first live satellite broadcasts – an exchange between Australia and Japan called Over the Equator. During the live transmission, two cameras broke down in the Melbourne studios, and the remaining camera, having no other option, continued to track in on a go-go girl dancing in a cage, and then slowly zoom on to a big close-up of her navel and gyrating tummy as it was being painted as a flower… flower power and hippy days!

The following morning Tom and I woke to headlines across Australia that the ABC had transmitted an obscene program to Japan. Alarmed that the ABC seemed to be acknowledging the charges to both media and Parliament, without even checking the reaction in Japan, Tom and I tried to see the General Manager to explain what happened. No luck. So we decided to phone our counterpart producer in Japan. Denied offices and phones (we had been suspended from duty), Tom and I got two bags full of two-shilling pieces from the bank, went to the public phone booth at the William Street Post Office, explained to a bemused international operator that it would take a long time for us to insert the coins required for an overseas call, and eventually spoke to our Japanese colleague. There had been no reaction in Japan. What we remember most is that at the end of the conversation, the Japanese producer said: ‘Tell them not to worry. There are much more interesting things in Tokyo we could have showed Australia.’ The incident became known as The Great Navel Scandal. To this day, I still feel a wicked frisson at having been associated with Tom in the only program that ran off the top of the program classification chart beyond R and X, to the unimaginable O for Obscene. Of course, it didn’t deserve the notoriety. It was pretty tame really by the sexy standards of the day – just a reminder of the underlying conservatism against which Tom continually flung himself.

Tom’s gifts to his craft and to us were his high intelligence, honesty, a cool, editorial and analytical savvy in the hot business of creative production, honourable dealings with the subjects of his programs, real flair, hard work, and courage.

For all Tom’s flamboyance and outspokenness there was in him a deep still centre of compassion and humanity, the qualities that most enduringly marked all his work and his life.

His friends and colleagues of these early days, would, I am sure, want to say with me:

'Dear Tom, thanks for the tumultuous journey beside you, for the intellectual stimulation, and for the way you stabbed away at injustice, hocus-pocus, cant, bad argument, the shabby, and the incautious – and thank you for the imperishable gift of your friendship'.

Robin Hughes:

I’m here today to speak on behalf of the very many of us who were mentored as young filmmakers by that clever, creative, crazy iconoclast Tom Manefield. Some knew Tom while working on Chequerboard, the programme with the sub-title ‘people in the situations that shape their lives’. And working in that situation certainly shaped our own lives forever.

Others learned from Tom during his tempestuous and very productive years at Film Australia.

For me it was both.

Chequerboard ’s enormous success as a pioneering program had a lot to do with the times. This was the late sixties, early seventies, and the times they were a-changin’. We were all in our twenties and keen to be part of it. Tom was the perfect leader- a little older, but totally committed to the idea of challenging established authority. We wanted to show the ABC audience the humanity of the fringe dwellers, to normalise the marginalised. It’s hard to believe it now but this was the first time that television docos were filmed directly with the people actually experiencing a situation, rather than with the experts who were studying them.

There were so many firsts. We did the first program in a prison talking to prisoners, the first where gay people spoke for themselves and then there was the day that a researcher came back from the Northern Territory and said, ‘You won’t believe this but they’ve been taking light-skinned babies away from their black mothers’. And so My Brown Skin Baby They Take Him Away was made with songster Bob Randall. That was the late sixties; it took a long time for action on it, but that’s when the issue was first brought into public consciousness.

When we filmed those universal human experiences like births, deaths, and marriages it was always to compare the haves and have nots. And who can forget Tom’s catch cries at the daily rushes in the bowels of the Gore Hill building: ‘compare and contrast’, ‘keep your options open’ and, of course, ‘don’t be afraid to go too far!’

Tom loved for us to film conflict or intimate revelations – real drama – but he had a fine intellect and he knew that good research would ensure that we were at the same time covering broader social issues. Under Tom we were never just a tell-all tabloid program. And although going too far often got him into trouble, he was committed to work of real quality. How we miss such leaders in television today!

Tom had many passions but his principal love was for his son Tim. One day he told me that he was in conflict with Tim’s kindergarten teacher, who made the kids say grace before lunch. Public education should be secular, declared atheist Tom, and stormed up to the school. But poor little Tim was now put out in the corridor for the grace. ‘Watch out,’ I said, ‘you’ll turn that boy into a Jesuit’. It was the wonderful, sane Nan who came to the rescue. Tim could say ‘Thank you mummy for the sandwiches’ while the others thanked God.

When I was forced to leave Chequerboard – no such thing as maternity leave then – Tom displayed another talent. He knitted my baby a pair of booties. Of course they were black.

Soon after, Tom left the ABC for Film Australia and he called and persuaded me to work there too, by pointing out that life as a producer would be more compatible with my new role as a mother. This move from interviewing and directing to producing, initiated by Tom, changed the course of my life for the next couple of decades.

At Film Australia, Tom was once again at full throttle, the entrepreneur of its move into effective educational filmmaking and continuing his pioneering concerns for Indigenous issues, with films like Walya Ngamardiki (The Land My Mother).

As always with Tom a new generation of young talent was developed in the process. I haven’t named names today because there are just too many of them, but Tom’s protégés form a rollcall of some of Australia’s finest filmakers, many of whom are here today.

Producers’ meetings were hilarious. Tom could never resist a stoush, especially with the bosses. As Storry said, he was ruthlessly honest and passionately uncompromising in his stances. There was a lot of conflict with those in charge. How very much Tom loved to stir things up. I remember the terrible day when it came to a head and we stupidly, ridiculously, lost him to the taxi industry, where of course he flourished, gave up the grog, and found contentment.

As I recall, the only film Tom directed as well as produced for Chequerboard was about death and dying. I interviewed it, pregnant at the time. After a moving and inspiring morning filming with terminally ill people, Tom turned to me and said: ‘It’s coming to us all and we don’t know when. It’s the new life that matters’ – and he patted my baby bump. Tom adored children.

Tis all a chequerboard of nights and days

Where Destiny with men for pieces plays:

Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays,

And one by one back in the closet lays.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.