The story behind the photochemical restoration of more than 100 films and fragments in the Corrick Collection, which toured Australia, South-East Asia and Europe between 1897 and 1914.

The story behind the photochemical restoration of more than 100 films and fragments in the Corrick Collection, which toured Australia, South-East Asia and Europe between 1897 and 1914.

For an introduction to the Corrick Collection, see On the road with the Corricks.

This blog refers to the photochemical restoration of the Corrick Collection. Learn about the 2021 NFSA Restores digital restoration.

When restoration began in 2006, an initial examination of the nitrate prints indicated that while there was surprisingly little image decomposition, some fragments were missing, others were brittle and had suffered significant shrinkage and buckling. Repeated screenings had resulted in scratches, missing perforations, tears and damaged heads and tails.

The first step in the restoration process was to identify the original films. ‘It was a real challenge to sort out exactly what was what, then order and match around 140 complete films and fragments,’ says project manager Sally Jackson. ‘In many cases there were no titles and the films ended abruptly. After a lot of detective work, we managed to identify most titles, but sometimes there just wasn’t enough film left.’

In 2007, NFSA curators showed an unidentified fragment from the Corrick Collection to British film scholar Ian Christie. After extensive research, Christie confirmed his initial suspicion that the ten-minute edited footage was from Charles Urban’s travelogue Living London (1904) – a film previously believed to have been lost. The scenes of daily life in the British capital caused a sensation in Australia, with an estimated audience of 500,000 seeing the film only months after its 1906 release.

Excerpt from Travelogue Living London (Charles Urban, England, 1904). NFSA title: 748390. Please note this clip is silent.

Once identified, films were forwarded to the NFSA’s audiovisual conservation unit for repair, frame by frame. The next step was to determine, given the fragile condition of the footage, which processes would best support the film-to-film copying required to produce negatives and high quality release prints suitable for screening.

The task of copying and printing each film was entrusted to the NFSA’s Motion Picture Laboratory (MPL). The original footage was run through a customised Debrie optical wet gate archival printer to generate two 35mm black-and-white polyester negatives. One negative was used to make screening prints and the other stored for preservation.

The poor physical condition of aged film, combined with thick overlapping splices and smaller perforations than the modern standard, necessitated some creative copying solutions and modifications to the printer. In the case of Pathé’s Cache-toi dans la Malle! (1905, Keep it Straight!) the heads and tails had to be printed separately and passed backwards through the printer to avoid breakage. Says MPL’s Trevor Carter, ‘It’s a nerve-wracking process which can take up to two hours for 300 feet (over 90 metres) of film, with two people coaxing the fragments through the machine.’

The copied fragments were then meticulously cut and spliced to ensure that the negative reflected the frame order of the original print. Next, the film was graded to ensure accurate picture quality and transferred, along with the grading file, to a BHP contact printer for the production of a polyester release print.

To mimic the luminous colour of the original titles and intertitles of the black-and-white films in the Corrick Collection, Carter and laboratory manager Steve Clark went back to early Kodak manuals and drew on contemporary research. Through a process of experimentation they were able to use the aniline coal dyes of 100 years ago to replicate similar effects on the polyester release prints.

Prints containing long segments of toned, tinted or stencilled colour were copied to black-and-white negative film before being sent to leading film restoration specialist Haghefilm Conservation in Amsterdam. Haghefilm produces 35mm colour prints using the Desmet method – the most accurate process available for re-creating the colouring effects typical of silent films.

‘It’s a compromise’, says Carter. ‘It’s our job to replicate exactly what we find on the original print, but modern colour film can’t capture the vibrancy of tinted and hand-stencilled film. It will always be an approximation.’

Nonetheless, the restoration process has bridged the gap between past and present, bringing the new media of another era to contemporary audiences, filmmakers and artists.

The NFSA will continue to work with Leonard Corrick’s son John to research the films and the story of the Marvellous Corricks.

Magnifier used to view the condition of films prior to repair, NFSA Canberra, 2011

Audiovisual conservator John Taylor uses a winder to examine the contents and condition of a film, NFSA Canberra, 2010

Repairing damaged perforations with perf tape, NFSA Canberra, 2010

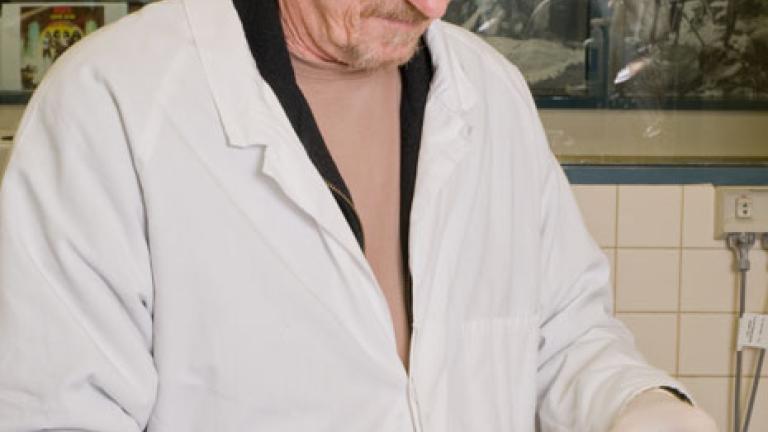

Film technician Trevor Carter prints black-and-white negative to positive film on the Debrie wet gate printer, NFSA Canberra, 2011

Film technician Bruce Cowell mixes aniline dye to match a tint used in silent film production, NFSA Canberra, 2011

Tank testing the aniline dye on a sample film, NFSA Canberra, 2011

Bruce Cowell and Trevor Carter tint a length of film in the film processor, NFSA Canberra, 2011

Tinted film exits the processor in the final phase of the tinting procedure, NFSA Canberra, 2011

More about the Corrick Collection and the Corrick family:

‘The Living London Boom’, Sally Jackson, Senses of Cinema, Issue No. 49, March 2009

Trove – Corrick family musicians

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.