South Australian Film Corporation

October 2012 marked the 40th anniversary of one the great milestones in the modern Australian feature film industry: the establishment of the South Australian Film Corporation, by then-Premier Don Dunstan and its founding CEO, Gil Brealey. This was the pivotal moment of the Australian cinema renaissance; one state government’s pro-active screen policy finally pushed our cinema past earlier exploitations of Australia as a picturesque location, or the hesitant prods to local production of the mid- to late-1960s and early ‘70s.

Brealey’s brief from Dunstan was to build not just a film industry, but a film culture in Adelaide (as suggested by the ambitious claim in some of the corporation’s ads of the early 1970s that the SAFC provided ‘Total Film’). It was an enterprise that would lead the Australian film industry back into regular and sustained production, to international critical appreciation and local audience respect.

The first part of our 40th anniversary retrospective began in 2012 with a look at the SAFC’s classics and milestones of the late 1970s. Despite occasional local political controversy and the odd filmmaking misfire, the titles that rolled out of the SAFC’s Hendon Studios in its first years are now legends of the Australian screen: Sunday Too Far Away (1975), Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Storm Boy (1976) and Breaker Morant (1979); or canonical Australian films which the SAFC indirectly nurtured, like The Last Wave (1977) and Gallipoli (1981). The SAFC also promoted an almost film studio-like roster of directing talent, giving established directors like Peter Weir and Bruce Beresford entrée to international success.

Part two looks at the SAFC in the 1980s and until it was fully corporatised in 1994. This was a much less remembered and more difficult period for the Corporation, just as it was generally for Australian cinema. After Breaker Morant the gloss began to rub off, as our cinema moved from the halcyon days of the 1970s renaissance into the hard realities of sustaining an industry through the 1980s. The SAFC particularly had to negotiate a policy shift from films where it was almost a film studio to ones where it was mostly a financier and production facility.

This was the new world of the ‘10BA’-era deal, as well as that of a government agency working in a market-orientated political and cultural environment. Some of the SAFC’s best work at this time was for TV, like the 1987 telemovie Call Me Mr. Brown.

Of the cinema features, some of the greenlighting and production partnerships seemed even then to be bad calls. Some still do. But in hindsight, some of the features with which the SAFC was associated are underrated; especially a number of projects that focused on the teen and youth market (1982’s Freedom, 1985’s Playing Beatie Bow, and 1990’s Struck by Lightning). Others are far more interesting now we’ve distance from the battles over their making (like the Antony I Ginanne produced The Survivor, from 1980).

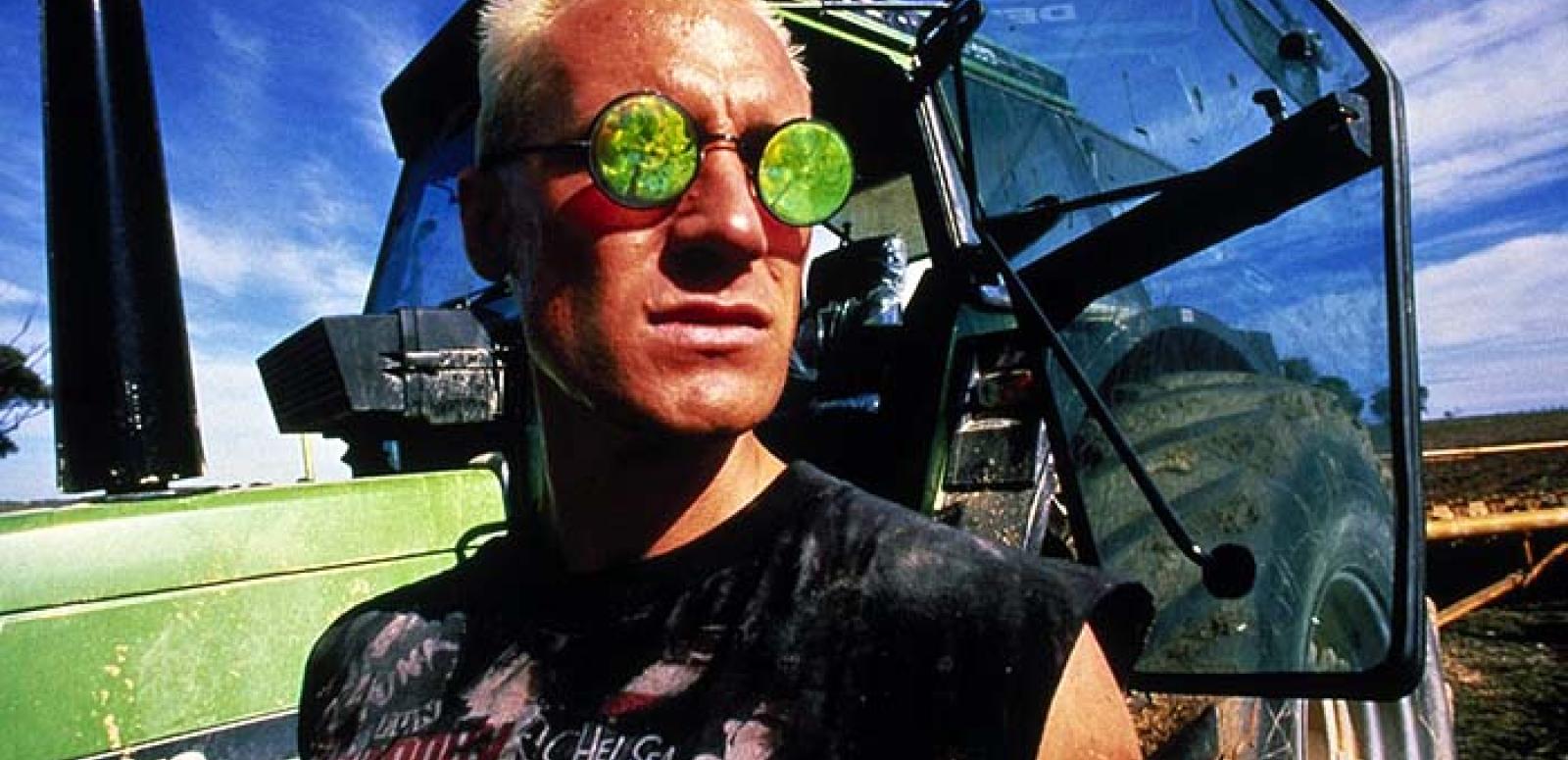

It was perhaps most important that the SAFC was nurturing a new generation of filmmakers. The 1980s sees the first features of a pre-[legacy-smartlink:Shine] Scott Hicks, who worked as an assistant on some of the SAFC classics of the 1970s, and also of Rolf de Heer, whose [legacy-smartlink:Incident at Raven’s Gate] (1988) remains one of the great Australian sci-fi films.

Total Film is presented with thanks to the South Australian Film Corporation. Selected titles are courtesy the NFSA’s Kodak/Atlab and Deluxe/Kodak Project collections. Pictured: Incident at Raven's Gate.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.