West Australian Aboriginal Performing Arts

This profile showcases West Australian Aboriginal performing arts and the collections of plays, music, dance and festivals held by the NFSA. Anna Haebich introduces the works and their directors, writers, artists, actors, musicians and dancers in a brief history that highlights their unique contributions to performing arts in Australia.

Anna Haebich was an NFSA SAR Fellow in 2012. She is a John Curtin Distinguished Professor at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia. Her current research project is to document Aboriginal performing arts in Western Australia, past and present.

Warning: This collection profile contains names, images and voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Introduction

Western Australia has a vibrant Aboriginal performing arts scene that embraces Aboriginal ways of knowing and doing and the very latest trends in contemporary performance.

Noongar performer and playwright Richard Walley explains:

Our theatre was corroboree and dancing. It’s the first form of theatre in Australia and it’s the oldest form … Theatre has been here for years because Aboriginal people had the dance and the music and the songs … the first operas … the first musicals were done by Aboriginal people. So it’s nothing new.(1)

Knowing about this rich heritage deepens our appreciation of the imaginative power of Aboriginal performance in Western Australia and the contributions of its practitioners nationally.

Mapping performance

Apart from the lives of a few famous performers, the backstory of performing arts in Western Australia is not well known. The state is a vast space with a sprinkling of people outside the capital of Perth. Of 2.2 million residents 77,000 are Aboriginal; of these, 28,000 live in the south, mainly in Perth. Many communities still live on their traditional Country.

Despite a cruel history of dispossession and colonisation Aboriginal cultures have survived. For creative artists there is a rich cultural field to draw on and inspire: the diversity of Aboriginal languages, Kriols and Aboriginal English; the rich oral traditions of storytelling and history; the unique styles of humour; and the treasures of dance, art and design.

These cultures all vary across the boundaries of regions – Noongars (south-west), Wongai (Goldfields), and Yamatji (Pilbara) and named language groups in these regions and the Kimberley – adding to the exciting possibilities for creation and performance.

Overview

Colonisation undermined Aboriginal performance and pushed what survived underground. Corroborees were sometimes staged for settlers who framed what they saw according to their own preconceptions and imaginings. In Western Australia special laws like the 1905 Aborigines Act segregated black from white and subjected Aboriginal people to cruel deprivations, humiliations and traumas. In such times community performance in ceremony and for entertainment reinvigorated spiritual strength and provided much needed joy and relief.

It was only from the 1970s that a new era began and Aboriginal performers across the country began to move to front stage. Armed with the new freedoms of citizenship and the agency of grassroots Aboriginal organisations, they began to push through old barriers to perform according to their own cultural styles and frameworks to appreciative Indigenous and white audiences. The surge of experimentation and innovation accelerated into the present, changing forever the face of performing arts in Australia.

Aboriginal people in Western Australia played a vital role in this. Artists there had a storehouse of cultures and histories largely unknown to outsiders and they drew on these to create a vibrant culture of theatre, music, dance, film and festivals.

Smoke from campfires still burning at the Tent Embassy, Old Parliament House, Canberra, 2012. Photograph by Anna Haebich

The driving themes in Aboriginal performance from this time around the nation were celebration of Aboriginal cultures and political protest over the legacy of colonisation and continuing injustice. In Canberra in 1972 the Aboriginal Tent Embassy triggered innovative ways of protesting that challenged, entertained and sometimes shocked as Black Theatre groups performed ‘sketches and street theatre … in hotels, in lounges of pubs, in the marches … all the political demonstrations’(2). Aboriginal performers in Sydney and Melbourne quickly notched up a series of Aboriginal ‘firsts’ in film, theatre and television marking the beginning of ‘Indigenous self-representation and self-empowerment in the arts’(3).

The first national Aboriginal performing arts workshop held at the Black Theatre in Redfern in 1975 acted as a catalyst for spreading the performance movement and participants became trailblazers back in their home communites. The film of the workshop, Tjintu Pakani: Sunrise Awakening (1976, director Ande Reese-Kindryd) is in the NFSA collection (NFSA title: 529325).

Aboriginal people in Western Australia joined in these national events. Some travelled east to join the Tent Embassy protests; others organised Black Power action at home. They gave their own spin to marches and events on issues from land rights to Aboriginal deaths in custody. The celebrations of 150 years of white settlement in Western Australia in 1979 gave further cause for protest but it was the government’s determination to force the drilling of sacred sites on Noonkanbah Station in the Kimberley from the late 1970s that incited national and international condemnation.

Protest steamrolled on into the 1980s with the state government’s botched handling of the 1984 Seaman Land Inquiry and then of the death of John Pat in Roebourne Prison in 1983. In 1988 Aborigines in Western Australia joined in protests against Australia’s bicentenary celebrations. Further political turmoil followed the publication of the findings of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and the 1997 Bringing Them Home Report on the Stolen Generations and the triumph in 1992 of the Mabo case.

Revitalising forces for Aboriginal cultures, especially in remote areas, were Aboriginal media and language centres. Both supported cultural projects and maintenance of Aboriginal languages. Goolari Media, set up in Broome in 1991, was a catalyst for the local music scene. In the south new language centres began recording the Noongar language. Aboriginal television expanded rapidly from the mid-1980s with CAAMA and Imparja transmitting from Central Australia and the development of other outlets.

Mainstream media responded to recommendations in the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody to adopt policies for appropriate representation of Indigenous issues and training programs for Indigenous people. This contributed to growing Indigenous control of representation and access to work in the industry4. There were also new government supports for film, principally the Indigenous Branch of the Australian Film Commission. Established in 1993, it funded projects like the From Sand to Celluloid initiative for emerging Indigenous filmmakers.

These developments spurred the wave of Aboriginal theatre and documentaries in Western Australia from the 1980s. The exciting new developments in performance – Noongar theatre and Broome musical theatre – emerged from this mix of politics and culture. The groundbreaking productions brought in Aboriginal ways of doing and knowing to transform mainstream theatre. They gave a new status to Aboriginal theatre in Australia and produced a new generation of outstanding actors.

Increasingly, Aboriginal people were in front of the camera and directing on stage. Performers were quick to take advantage of the opportunities and greater accessibility and affordability of new digital technology. Young people began producing their own exciting low-budget works outside the mainstream and there was greater potential for new institutional and community partnerships for creative works, repatriation of materials and local festivals. The establishment in 2007 of National Indigenous Television (NITV) expanded the niche for these and other creative productions.

Archival Materials

Archival footage of early Aboriginal performances from Western Australia is scarce in the NFSA collection. The logistics of travelling there discouraged most filmmakers although some welcomed the challenge. Whether Aboriginal people participated willingly in the few films made is not clear but their performances make compelling viewing.

There is some footage of impromptu corroborees performed by workers on pastoral stations in the remote north but for cultural reasons we cannot include this here. Instead we see clips of Aboriginal men demonstrating their physical skills and prowess to the camera.

The documentary Chez les Sauvages Australiens was filmed in the Kimberley by William Jackson during the 1917 North-West Scientific Expedition of Australia. In one scene young men perform a convincing simulated attack, rushing with spears held high towards the camera.

The MacRobertson’s Round Australia Expedition of 1928 (NFSA title: 138660), sponsored by the flamboyant Chocolate King and philanthropist Macpherson Robertson to entertain the people of the outback, travelled overland from Melbourne into the Kimberley. They also captured Aboriginal men on camera for entertainment back home including Aboriginal workers at Moola Bulla Government Station out from Halls Creek in the East Kimberley in an impromptu performance for the camera.

Aboriginal men breaking in horses and donkeys and racing them at Moola Bulla Government Station, East Kimberley. Round Australia with the MacRobertson Expedition (1928). NFSA title: 138660

Documentaries

Political clashes and disclosures of West Australia’s dark history of colonial violence drove the growing list of local Aboriginal documentaries created from the 1970s.

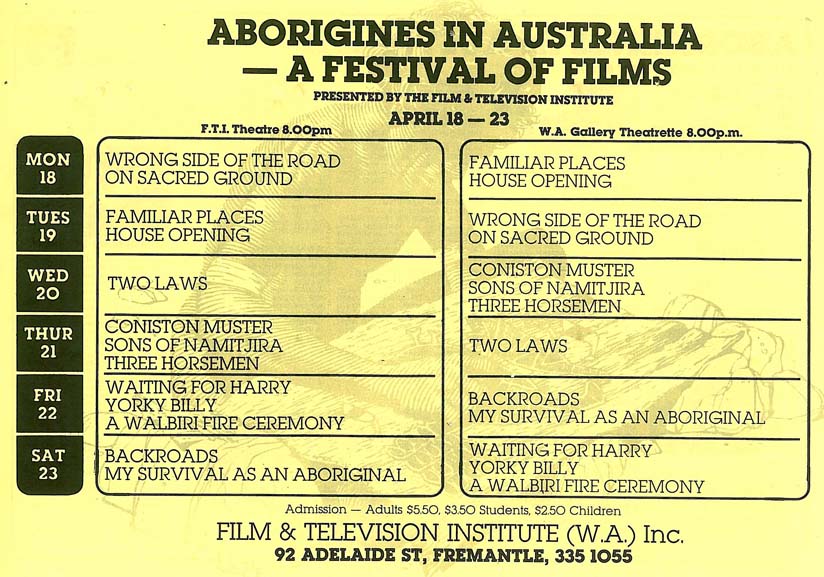

The beginnings were humble enough: the state’s first Black Film Festival (1979, NFSA title: 516903) included one local film featuring Ken Colbung as Yagan (director Michael Edols’ Mowanjum films were strangely absent) while Aborigines in Australia – a Festival of Films in 1983 showed only one West Australian film out of 26 featured documentaries.

Aborigines in Australia – A Festival of Films (1983). Courtesy Film & Television Institute WA. NFSA title: 516159

The majority of these documentaries had non-Aboriginal directors. They were nevertheless a significant step forward. For the first time Aboriginal communities were negotiating with directors for films to be framed by Aboriginal perspectives and for oral histories to be brought together with government archives and new historical research. These films are now invaluable historical records. They share a certain style, combining documentary conventions with local Aboriginal content and viewpoints. There are narratives of the Aboriginal struggle against destruction and dispossession; frequent reenactments of events; eyewitness testimonies; shots of damning archival documents; and the representation of centralised control over Aboriginal people through re-creations of the Chief Protector’s office in Perth, complete with typewriters pounding out directives to the field.

Documentaries from this period held in the NFSA collections include On Sacred Ground (1980, director Donald Crombie) with lawyer Ribner Green (Djaru) outlining the land rights movement in the Kimberley and recounting the heroic fight to save Noonkanbah sacred sites (NFSA title: 32720). Munda Nyuringu (1983), directed by Jan Roberts and Bob Bropho (Noongar), demonstrated the tragic impact of mining on Wongai communities in the Goldfields (NFSA title: 54090). David Noakes directed How the West Was Lost (1987), covering the famous 1946 Pilbara strikes by Aboriginal station workers and their aftermath. Precious archival footage and eyewitness testimony captures the vision of organisers Dooley Bin Bin, Peter Coffin and Don McLeod and their daring opposition to the pastoralists’ punitive treatment and government interventions to break the strike.

Sam Coppin talks about ‘four dollars a fortnight’ in How the West Was Lost (1987). Produced with the Strelley Aboriginal community. Directed by David Noakes. Produced by Heather Williams, David Noakes and Paul Roberts. NFSA title: 51482

In Black Magic (1988) directors Frank Rijavec and Paul Roberts recorded Noongar men recounting stories of the successes of their outstanding sportsmen and how they used this to fight against racism, oppression and poverty.

In the same year director Deborah Howlett worked with Heather Vicenti (Wongai) on the documentary A Little Life (1988), a moving account of the life of Heather’s son whose tragic death was investigated by the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (NFSA title: 660385).

Aboriginal people began taking more control of the camera and the first local documentaries by Aboriginal directors appeared in the 1980s. Wayne Barker (Yawuru, Djabbirrjabirr) made Cass No Saucepan Diver (1982) about his grandfather’s life in Broome’s pearling industry as a film trainee with the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (now Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies; NFSA title: 777668). The first film directed in the west by an Aboriginal woman was Tracey Moffatt’s Moodeitj Yorgas (1989) with interviews of prominent local women including author Sally Morgan, singer Lois Olney and activist Helen Corbett (NFSA title: 629203).

The groundbreaking documentary Exile and the Kingdom (1993) was the product of a new form of collaboration with director Frank Rijavec working under the control of the Juluwarlu, Ngarluma, and Yinjibarndi people living in Roebourne in the Pilbara. Frank Rijavec explained at the time, ‘It’s not a documentary about Aboriginal people, it’s by Aboriginal people. I was just there providing the filmmaking skills and putting it all together … this is not an anthropologist’s film. It’s the Aboriginal people saying “this is our culture, its alive, it’s ours and here it is.”’(5)

The documentary uses their storytelling rhythms and concepts of mythological time to trace the narratives from before recorded history to the destruction of colonialism and the devastating impact of forced removals from Country to towns to explain why return to their homelands is absolutely vital.

Exile and the Kingdom won wide critical acclaim and was congratulated for challenging audiences to ‘alter their way of seeing and hearing, to force them to reflect critically – both on the act of representation and, more crucially, reality itself’(6) (NFSA title: 233684).

The Coolbaroo Club was also a new form of collaboration, between non-Aboriginal director Roger Scholes and Aboriginal academic, researcher and creative writer Steve Kinnane (Mirrawong), and writer Lauren Marsh. Kinnane grew up in a Perth Aboriginal household whose residents and many visitors frequented the Coolbaroo dance club and were politically active in the Coolbaroo League during the 1940s and 1950s. He also researched government archives on the subject and had a sophisticated knowledge of film.

Critics praised The Coolbaroo Club (1996) as ‘stunning and beautifully crafted’, ‘a lushly textured glimpse of an Australia … which most of us didn’t know existed’. Novelist Robert Drewe wrote that ‘a copy should be obtained by every school in the country’(7) (NFSA title: 288331).

The Coolbaroo Club (1996). Directed by Roger Scholes. Source: Ronin Films. NFSA title: 288331

Noongar theatre

During the 1970s and 1980s Noongar theatre burst onto the national stage with an aesthetic and style that would dominate Aboriginal theatre into the new century. The irony was that most West Australians had no inkling that a distinctive Noongar culture and history existed. Noongar theatre sought to remedy this ignorance.

The roots of this theatre lay outside the conventions and traditions of Western theatre, coming from a vision steeped in Noongar ways of storytelling, narrative, expression, movement, language, music and dance. The intention was to create a theatre of Noongar urban culture using its frames of knowledge, values, emotions and experience and explanations of the past and present. This was translated into the conventions and spaces of mainstream theatre while also challenging these traditions(9).

The vehicle for storytelling was the urban Noongar extended family with its tragedies, flaws and heroes, using Noongar language, family characters and humour with Noongar actors playing out the roles of family members. The plays presented a Noongar reality where the mythic world broke easily through into daily family life, taking the form of dance and music and co-existing with the realist family drama.

Collaboration was vital to this new theatre, also being an essential process in Noongar ways of working. The cast was made up of untrained Noongar actors with shared family and cultural ties. They came from the same background and knew the stories and culture and had lived the events of the play. They could intuitively work themselves into the characters and release the drama of their own lives.

Playwright, poet and actor Jack Davis pioneered Noongar theatre in his major plays Kullark (1979), The Dreamers (1982) and No Sugar (1985). The works were grounded in his own family history and collaboration with family members, in particular his sisters Dot Collard (who acted in all his plays), Ethel, and Barbara Henry, and his niece Lynn Narkle.

Davis’s parents were of the Stolen Generations, having been sent from the north-west to institutions in the south. Their children were fortunate in being able to attend school and become literate at a time when Noongar children were excluded from state schools. For a time Davis lived at the infamous Moore River Native Settlement, which provided inspiration for his theatre. With his mother and siblings he learned about Noongar language and culture from custodians in the Bennell and Collard families in the town of Pingelly.

In Perth during the 1960s and 1970s Davis became politically active in state and federal Aboriginal political organisations. A self-taught poet he learned the power of theatre as a political medium and attended the 1975 Black Theatre workshop in Redfern and appeared in the film of the workshop, Tjintu Pakani: Sunrise Awakening (1976), working on an early play. Vital to Davis’s work was his partnership with Andrew Ross who directed and worked with him on most of the plays. For the play No Sugar, that told the story of the forced removal of an entire Noongar community from the town of Northam to Moore River Settlement during the early 1930s, the two undertook detailed research in the archives of the Aborigines Department, collected Noongar oral histories and even travelled the track some families walked along from Northam to the settlement.

Sadly little known film footage of these plays survives. The NFSA has only a small, eclectic collection of Davis’s work: a recording of iconic Australian actor Leonard Teale reading a selection of his poetry; some interview material; his appearance in the Redfern workshop in 1975; and an excerpt from The Dreamers in 1984 documentary Milliya Rumarra Brand New Day (directors David Noakes and Bryan McClellan, NFSA title: 251660).

Excerpt from 'The Dreamers’ in Milliya Rumarra Brand New Day (1983). Produced and directed by David Noakes and Bryan McLellan (deceased)NFSA title: 251660 .

Davis’s plays achieved national and international success in Europe, Canada and the United States. The Dreamers premiered at the 1982 Perth Festival and then toured Australia. One Sydney critic described it as ‘the most important play seen in Sydney this year … it stands out as a cultural landmark’(9).

Noongar theatre revitalised a subdued local performing arts scene and inspired Aboriginal and other performers and playwrights across Australia. Davis’s plays influenced a new generation of writers like Glennys Ward, Richard Walley, Sally Morgan, Dallas Winmar and Archie Weller; actors Ernie Dingo, Lynette Narkle, and Dot Collard; and performer Richard Walley.

Richard Walley OAM (Noongar) leads the Middar Aboriginal Theatre and Dance Troupe that has toured and performed before millions of people in 32 countries. He is a truly all-round artist: director, actor, designer, playwright, choreographer, dancer, singer, didgeridoo player, visual artist, advocate for Aboriginal arts and rights activist, and Noongar cultural leader.

Richard’s work is well represented in the NFSA collection with various cassette and CD compilations and videos including Didgeridoo in Deutschland where he performs in Berlin with the Australian classical composer George Dreyfus, and the workshop for his play Munjong (1989 NFSA title: 123187 ; 1990 NFSA title: 675401). His play Coordah is representative of Noongar theatre, dealing with urban families and being rich in Noongar language, knowledge, storytelling and humour as the following excerpt shows:(10)

Nummy: Well, after about a hour I said to them wetjelas, ‘Put your guns away. I’ll show youse how to catch a ‘roo.’ … Anyway, they laughed at me and said, ‘OK, smart arse – show us what you can do!’ So I picked up two stones and walked towards the creek … At the bottom was this big boomer…

Ginna: And you killed him?

Nummy: No. He was too big. … I stayed behind the bush … then soon, a smaller one hopped along. When he reached the water … I just whistled and the ‘roos stood up looking around. Then I threw one of the stones, high up in the air and they looked up watching it. … Then I threw the other stone and hit the ‘roo fair in the head – killing him stone dead … I hit a duck too. It was flying past at the same time.

Broome music

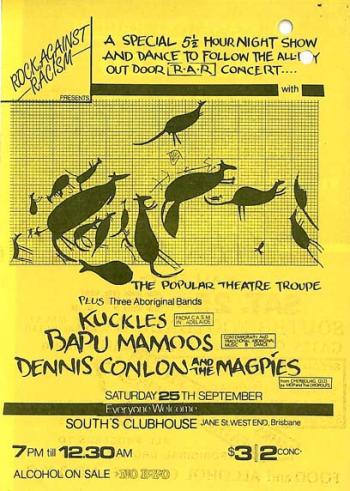

Broome music is a vital part of the rich range of musical styles and traditions in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Performers like Broome’s Pigram Brothers (previously Kuckles) are internationally famous, while others are well known to local communities as song men and women and contemporary performers. The NFSA has a wideranging collection of Kimberley music.

Examples include: Rimijmara: Traditional Aboriginal Music: Music of the Wandjina People by Wunambul singers (1997 NFSA title: 81433 ); Singing Up the Country: Traditional and Contemporary Songs From the Kimberley, Western Australia (1993 NFSA title: 243411 ); Didj’un Singer Songwriters from the Kimberley (1998 NFSA title: 747255 ); Blackfellas film soundtrack (1993 NFSA title: 242384 ); and themed compilation Cry Stolen (2007 NFSA title: 810585 ). Some singers, bands and dancers appear in films and videos: for example singer Allan Barker and Jimmy Chi and Kuckles in Milliya Rumarra Brand New Day (1984 NFSA title: 251660).

The iconic Pigram Brothers band plays an eclectic mix of country folk and rock that is part of the Broome Sound that draws on a vibrant mix of the town’s Aboriginal and multicultural influences. Many of the band’s songs, like ‘Saltwater Cowboy’ about pearling crews returning home to port, have become Broome standards.

The band works collaboratively with other musicians, playing at political events like an early Rock Against Racism in 1985, and performing a vital role in Broome musical theatre as performers, composers and co-producers.

The song ‘Sooner be Dreaming in Broome’, written at the Adelaide Centre for Aboriginal Studies in Music in the 1970s, is about being homesick for the smells and tastes of home and in particular the Pigram family’s famous fish soup and rice.

This light-hearted SBS foodie clip gives the backstory to the song showing members of the Pigram family at the beach catching fish and cooking the soup.

Making fish soup and rice in Broome: The Food Lovers’ Guide to Australia – Series 5 Episode 1 Copyright SBS 2005.

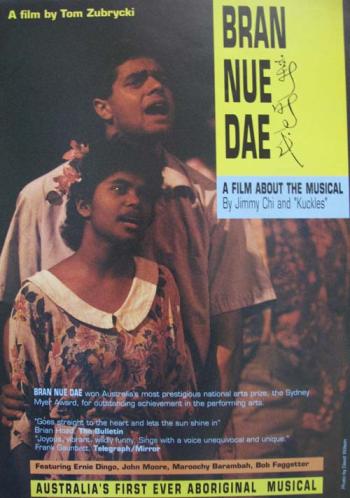

These various Kimberley musical influences helped shape the collaborations of Broome musicians like the Pigram Brothers, Stephen Baamba Albert, Mick Manolis and others working with Jimmy Chi to forge his vision of a vibrant new form of musical theatre. The results were the wildly successful musicals Bran Nue Dae (1991) and Corrugation Road (1996).

The style of Bran Nue Dae takes us back to our opening quote from Richard Walley that ‘theatre has been here for years … because the Aboriginal people had the dance and the music and the songs’. The musical is a celebration of Aboriginal performance in all its elements and all the influences that have come to bear on it. Mixed together are: Aboriginal dance, song and myth; Broome music, kriol, humor and storytelling; contemporary dance; and even popular film musicals like My Fair Lady (1964) and West Side Story (1961), viewed by Jimmy at the Broome Sun Theatre.

During a long gestation period from the 1980s until its first performance in 1991, Bran Nue Dae developed through collaborations and close relationships of friendship and trust between Jimmy Chi and his fellow Broome musicians, working with newcomers director Andrew Ross and contributing writers, managers, singers, dancers and actors. From this collaboration came a new musical theatre freed from mainstream theatrical conventions and driven by the celebration of Aboriginal culture and survival and the power of irrepressible humor and joyful performance.

Jimmy Chi has spoken of the many inspirations for his creative vision: his Nyul Nyul, Japanese and Scottish ancestry; the ‘time of wonder’ growing up in Broome and the cultural and musical influences there; the wrench of going to study in Perth and living in a Catholic hostel run by German priests; the pressure he felt at university to be a success and become assimilated; and the relief of returning home to Broome. These are all themes in the narrative of Bran Nue Dae (11).

Jimmy also talks openly about living with schizophrenia and the healing power of music in his creative works: ‘music was my therapy – a comfort, a spiritual source that made me write about all the pain that was in me about a lot of issues, and helped me to relate to the world again’. This was the inspiration for Corrugation Road (1996) that depicts this darker side of his life with humour and hope.

Political issues also shaped the narratives of the musical Bran Nue Dae and its powerful songs like ‘Listen to the News’. There were the angry protests over Noonkanbah, deaths in custody, the rapid development of Broome as a tourist town and then the Stolen Generations. The documentaries On Sacred Ground (1980) and Lord of the Bush (1990, Tom Zubricki, NFSA title: 558821) in the NFSA collection show the protests and heated emotions of the time.

Jimmy describes other more universal meanings of Bran Nue Dae: ‘It is the search for love and identity. It is a simple story where love and the joy of life triumphs against a background of mayhem and dishonour. It is my story but it is also yours and everybody else you know who seeks love and happiness in a world clouded by injustice.’(12) During the politically divisive events of the 1990s the musical provided a glimpse of the dream of reconciliation for the nation.

There is also a deep spiritual message based in Aboriginal values and beliefs, Catholicism and world spiritualism. Jimmy speaks of ‘raising awareness through music you’re exposed to in the performance, this other spiritual dimension in the play … Bran Nue Dae is a healing process.’ It is a parable: ‘Naked truth is too ugly. That’s why she must be dressed in the finery of parable.’(13)

Broome musicians and musical theatre are well represented in the NFSA collection. There are comprehensive recordings and video clips of the Pigram Brothers and the songs from Bran Nue Dae; documentaries and documentation about the theatre performances of the musical and of the feature film directed by Rachel Perkins; and interviews with Jimmy Chi. The script of Bran Nue Dae was published by Currency Press.

Aboriginal men with Jimmy Chi and Steve Pigram singing 'Bran Nue Dae’, Broome. Bran Nue Dae documentary, director Tom Zubrycki.

Bran Nue Dae revolutionised Australian theatre by creating a new vision of Aboriginal performance as cool, fun and exciting, and began a bright new era of success for those associated with it. The musical was instrumental in the formation of the Perth-based Black Swan Theatre Company as a multi-ethnic performance group for regional theatre involving Andrew Ross, Jack Davis and Jimmy Chi. Aboriginal dancer and choreographer Michael Leslie established an affiliated Aboriginal performance training school. Building on this success came Western Australia’s only Aboriginal performing arts company Yirra Yaakin, established in 1993 and now Australia’s leading Indigenous theatre company.(14)

The musical also launched and extended the careers of some of Australia’s leading Aboriginal performers: Josie Ningala Lawford, John Moore, Leah Purcell, Della Morrison, Ernie Dingo and Stephen Baamba Albert. Many of these artists also appeared in the feature film of Bran Nue Dae (2009), along with other local actors like Kelton Pell. Most are represented in the NFSA collection.

Festivals

Western Australia has a rich history of festivals celebrating and performing Aboriginal cultures. Two of the festivals held on the Perth Esplanade on the banks of the Swan River are represented in the NFSA.

The 1983 Aboriginal Arts in Perth Festival was billed as the first cultural event of its kind in Australia. People thronged to see the variety of performances by community singers, dancers and storytellers from Perth, Brisbane, Warmun (Turkey Creek), Mowanjum (Derby) and the Pitjantjara Lands. The festival also staged urban theatre with a performance by the cast of The Dreamers and music events with bands like Jimmy Chi and Kuckles singing Bran Nue Dae. There was also an exhibition of prisoners’ art introduced by artist Jimmy Pike, workshops demonstrating Aboriginal arts and crafts, and forums on cultural issues and education. Playwright Jack Davis commented in the festival brochure: ‘It’s a tremendous step forward in the revival of Aboriginal culture … We’ve been waiting for this nearly 200 years now’ (see Milliya Rumarra Brand New Day: Documentation, 1983. NFSA).

This now-historical festival was captured for posterity in the video Milliya Rumarra Brand New Day (1983). In a first for West Australia the directors, David Noakes and Bryan McLellan, trained an Aboriginal film crew to work with them. The documentary was launched in 1984 before audiences of Aboriginal men at Cannington and Fremantle Prisons, then at a special screening at the Film and Television Institute in Fremantle (produced and directed by David Noakes and Bryan McLellan, NFSA title: 251660).

The Kyana corroboree festivals held in Perth in 1991 and 1993 were a project of the Dumbartung Aboriginal Corporation. Festival coordinator Robert Eggington described the central theme as ‘cultural revival [to] strengthen future directions for our people and communities where communities can show and experience their rich Aboriginal heritage and cultural values’(15). They were Aboriginal celebrations that were planned, organised and performed by Aboriginal people (Dumbartung Aboriginal Corporation, Kyana Corroboree, 1993, NFSA title: 267127).

The Kyana festivals were ambitious in scope. The 1993 festival had exhibitions of Aboriginal organisations from around the state, varieties of bush foods, historical photographs and arts and crafts. There were dancers from Perth, Warburton, Broome, Kalumbaru and Mornington Island and performances by local and interstate rock bands, notably one of Archie Roach’s first performances of ‘Took the Children Away’, and statements from Aboriginal leaders on issues of concern.

Going digital

The 2000s ushered in an exciting new era in Aboriginal performing arts in Western Australia with more Aboriginal artists taking charge of representation at all levels. This followed trends around Australia. For example Screen Australia’s The Black List demonstrates the dramatic increase in Indigenous filmmakers nationally contributing to 9 feature films, 16 TV dramas and 275 documentaries from 2000 (16). There were new openings and audiences for Aboriginal performers with the establishment of the Indigenous owned and operated National Indigenous Television (NITV) in 2007. The breakthrough development was the advent of digital technology that revolutionised what could be done behind and in front of the camera, being less complicated, less expensive, more accessible, more immediate and altogether more attractive to a new cohort of Indigenous youth, and encouraging new partnerships between geographically distant organisations and communities.

West Australia had its first Aboriginal movie box-office hits in the 2000s demonstrating the national interest in local Aboriginal stories and performers. Phillip Noyce directed Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002) based on Doris Garimara Pilkington’s book about the heroic trek of three Aboriginal girls escaping from Moore River Native Settlement back to their families (NFSA title: 507777). The feature film Bran Nue Dae (2009) by Aboriginal director Rachel Perkins (Arrente) had a mainly Aboriginal cast and crew (NFSA title: 792648). On national television there was the SBS TV series The Circuit (2007) set in the West Kimberley (NFSA title: 740552).

Between 2000 and 2011 the outstanding Broome director, producer, writer, researcher, actor and documentary maker Michelle Torres (Yawurru/Goonyandi) worked on 15 documentaries, including Jandamarra (2011). Michelle works with stories and family and friends from Broome and the West Kimberley. She explains that her films have ‘a message for everyone from all walks of life, all cultures, religion, whatever. So when I have found one that pulls at my heartstrings, I know it will have the same effect anywhere in the world.’(17)

Her documentaries are well represented in the NFSA collection. The film Case 442 (2005) tells the story of Frank Byrne. Byrne was taken from his mother at the age of five and only learned late in life that his mother was subsequently sent to a psychiatric hospital in Perth, where she died 18 years later. The film tells how he brought his mother’s remains back to her country in the Kimberley. In this clip from Case 442 Frank Byrne ponders ‘what purpose’ there was for sending him to a mission and ‘wrecking’ his life and his mother’s.

Case 442 (2005) Directed by Mitch Torres. CAAMA Productions. Distributor Ronin Films. NFSA title: 747018

A new reflective style of documentary emerged in Burning Daylight (2007), a collaboration between director Warwick Thornton and dancer and choreographer Dalisa Pigram that records the stages of creating the contemporary dance performance Burning Daylight in Broome. The film begins with Dalisa seeking permission from local Aboriginal elders to use their dance elements in the performance, then discusses the inclusion of Asian cinema and African hip hop with comments from the dancers who come from Broome, Japan and the Western Desert. Concerning the performance Delisa observes, ‘To me contemporary Indigenous dance is mixing what comes from you with what you know and what you remember and what you have learnt along your way … contemporary Indigenous dance is what’s coming from you and your influences’ (NFSA title: 744669).

There were also new training opportunities for young Aboriginal filmmakers and crew in West Australian government-funded projects bringing them together with established directors and producers. The NFSA has works from the Making Movies Roadshow run by ScreenWest and the Fremantle Television Institute (FTI) in 2003 and 2004, including Old Days New Days (2004, director Mirima Dawang Woorlab-Gerring, Language and Culture Centre, Kununurra NFSA title: 688624) and A Place in the Heart (2004, director Billy Narrier, NFSA title: 688428).

Deadly Yarns was a collaboration between ScreenWest, ABC TV and the FTI to develop and showcase short films by Aboriginal writers, directors and producers including Miss Coolbaroo (2004, director Michelle White, NFSA title: 688376) and Weewar (2006, writer Kerri-Anne Kearing, NFSA title: 714020).

At present there are no examples in the NFSA collection of the growing list of experimental digital works by young Aboriginal filmmakers and animators. However the NFSA Indigenous Collections Branch works closely with communities to foster partnerships to enable them to deposit, access, exhibit, research and repatriate audiovisual materials and also to create their own works (18). A West Australian collaboration is with the Martu people of the Western Desert working on the Martu History and Archive Project (Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa, Western Desert Lands Aboriginal Corporation). In 2007 Martu elders who visited the NFSA were presented with archival sound and moving image recordings to take back to their community. The Martu Parnngurr Film Festival was another collaborative event (NFSA title: 765166). The NFSA collection holds sound and moving image recordings of recent Martu political projects filmed by Martu people.

Conclusion

Performing arts in Western Australia have a rich history. This collection profile has explored this history using works held in the NFSA collection that are linked to major developments and trends. We met some of the artists driving the productions that shape representations of Aboriginal people and their cultures and the networks of actors, directors, producers, writers, researchers, artists and communities who have worked together to achieve these creative visions. The hope is that this profile encourages further research into Aboriginal performing arts in Western Australia and inspires more Aboriginal performers in their quests. Also, that more West Australian Aboriginal artists will deposit their works at the NFSA so that its collection can become truly comprehensive and representative of the performing arts in Western Australia.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the NFSA for the SAR Fellowship that enabled this research, in particular the SAR ‘minders’ Vincent Plush, Jenny Gall and Ruth Hill for their patience and learned advice and Chris Guster whose NFSA research essay was a valuable guide (19). Also thanks to my partner Darryl Kickett for his patience.

References

1Walley, R 1990, Munjong, Victorian Arts Centre, Melbourne, NFSA title: 675401.

2Gerry Bostock cited in Wikipedia, ‘Black Theatre’, viewed August 2013 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Theatre_(Sydney).

3McNiven, Liz ‘A Short History of Indigenous Filmmaking’ on australianscreen, viewed August 2013 at http://aso.gov.au/titles/collections/indigenous-filmmaking/.

4Ibid.

5‘Movie Maxims Exile and the Kingdom Talking Frankly’, no other details provided, documentation file NFSA title: 342041.

6Mark Naglazas in The West Australian, no other details provided, documentation file NFSA title: 342041.

7Graham Nowland in The Western Review, July 1996; Ruth Hessey in The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 July 1996; Robert Drewe in The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 July 1996; documentation file NFSA title: 343587.

8Casey, M 2004, Creating Frames: Contemporary Indigenous Theatre, 1967-1990, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia.

9The National Times, 30 December 1983.

10Thompson, L 1999, Aboriginal Voices Contemporary Aboriginal Artists, Writers and Performers, JB Books Australia, Marleston, p 66.

11Jimmy Chi interviewed by James Murdoch (1992), Oral History, NFSA title: 289163.

12Ibid.

13Tom Zubrycki, 1991, Bran Nue Dae, NFSA title: 235013.

14Yirra Yaakin Aboriginal Theatre Company website, viewed August 2013 at yirrayaakin.asn.au/.

15Narrator Robert Eggington in Dumbartung Aboriginal Corporation, 1991, Kyana Corroboree [Perth 1993], NFSA title: 267127.

16Screen Australia 2010, The Black List: Film and TV Projects Since 1970 with Indigenous Australians in Key Creative Roles, Screen Australia, Sydney.

17Cited in Australian Film Commission 2007, Dreaming in Motion: Celebrating Australia’s Indigenous Filmmakers, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, p 66.

18‘Indigenous Collection’ on NFSA website, viewed August 2013 at http://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/indigenous-collection/.

19Guster, Chris 2011, ‘Keeping Our Story: 30 Years of Indigenous Media’ on NFSA website, viewed August 2013 at nfsa.gov.au/research/papers/2011/12/21/keeping-our-story-30-years-indigenous-media/.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.