The Kid Stakes

To coincide with its release on DVD and Blu-ray for the first time, John Brady explores the history of silent classic film The Kid Stakes (1927) – detailing how it was made, lost and then rediscovered.

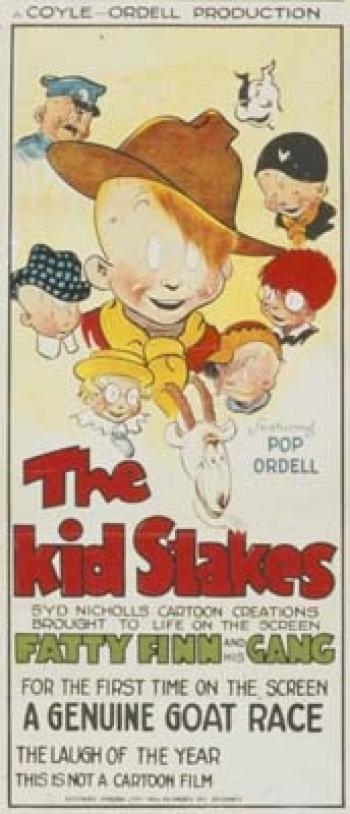

The Kid Stakes (1927) is one of the real gems of Australian silent-era cinema. Growing out of Syd Nicholls’ popular Fatty Finn weekly newspaper comic strip, the easygoing characters and likeable story had wide appeal to all ages, and with a charm that continues to entertain to this day. It appears to be the first significant children’s feature film produced in Australia. During the 1920s children’s cinema was limited to shorts and imported films.

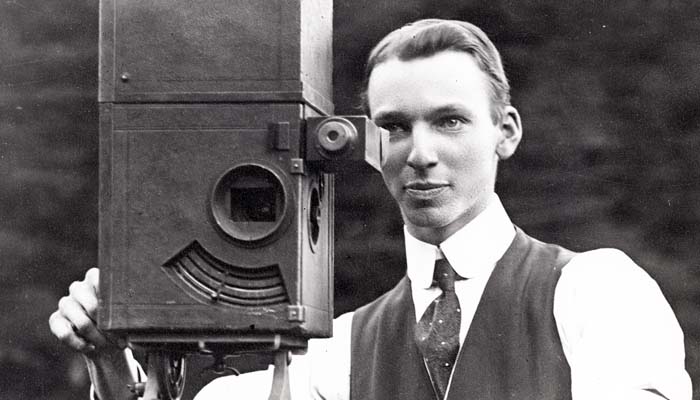

Comedy actor Tal Ordell, who had directed at least one two-reel (20 minute) short comedy film in 1921, directed The Kid Stakes in what was to be his only feature film as director. A stage actor and published poet, Ordell had starred in Beaumont Smith’s popular Hayseeds series of films. He also played Dave in Raymond Longford’s Dad and Dave comedies about country life, On Our Selection (1920) and Rudd’s New Selection (1921). Having worked under both ‘one-take’ Beaumont Smith, renowned for his quickies, and the more cinematic Longford, it is clear that Ordell chose to follow Longford’s style, recruiting his regular cinematographer, Arthur Higgins.

(L-R) Jimmy Kelly (played by Ray Salmon), Fatty Finn (Robin 'Pop’ Ordell) and Tiny King (Charles Roberts)

Ordell elicits fabulous performances from all the actors. He cast his six-year-old son Robin – known as ‘Pop’ – in the lead role of Fatty Finn, and assembled a wonderful selection of 5-10-year-old kids to play members of his, and rival Bruiser Murphy’s, gangs. One of these, Ray Salmon (who played Jimmy Kelly), in a newspaper interview at the time of the film’s first revival screenings in 1952, shared a handwritten letter from Tal Ordell which served as his ‘contract’ for the film, dated 11 November 1926:

"Your salary will be 7/6 per day on every day you perform before the camera, and fares to and from your home. If you will bring your fox terrier along I will also pay you for his services. You must be on time. Bring the following old clothes with you: 1 old coat, 1 pair pants, 1 coloured shirt, 1 pair of boots, 1 cap, 1 hat, 1 waistcoat, 1 towel and piece of soap. Also your lunch."

The film was mainly shot in the streets of Sydney’s inner-city suburb of Woolloomooloo, the mansions of Potts Point, Centennial Park and a paddock at Mascot (the emerging Sydney airport). With goat racing actually being illegal in NSW, the goat race scenes were filmed in Rockhampton in central Queensland. Tal Ordell himself appears in these scenes as the radio commentator.

Brisbane’s Wintergarden Theatre hosted the premiere on 9 June 1927 and the film travelled the national cinema circuit over the next few months. Reviews were generally positive and the film had modest success, while still being labelled as ‘just’ a children’s film.

After the original season of The Kid Stakes in 1927, Tal Ordell continued to work on stage and screen, acting in sound-era remakes of earlier silent films, including playing Ginger Mick in Frank Thring’s The Sentimental Bloke (1932). He increasingly worked in radio, writing children’s stories and a long-running serial Wattletown, in which he once again performed alongside his son Robin. But it is for The Kid Stakes that both Tal and ‘Pop’ are remembered.

1950s rediscovery

In the early 1950s, The Kid Stakes screened in three Sydney newsreel cinemas in a 19-minute cut-down version. Having apparently been found in a distributor’s archive, the film had been edited into a two-reel comedy ‘short’, for screening 11 times a day as part of a busy newsreel schedule. A Sunday Herald newspaper article from 7 December 1952 reports on a private screening given to Fatty Finn cartoonist Syd Nicholls and two of the children from the cast, now adults, that the distributors had managed to track down: Gwenda Hemus (who played Betty Briggs) and Ray Salmon (Jimmy Kelly).

At these newsreel screenings, the film happened to be seen by members of the Sydney University Film Group (SUFG), who were inspired to ‘rescue’ the film. With the support of the owner of the original print, Mr J Tayler of National Films, the SUFG undertook the task of reconstructing the film to its original length. They subsequently raised funds to create a duplication negative and this was then used to produce 35mm and 16mm screening prints.

The SUFG screened the full version of The Kid Stakes at the Union Hall in September 1954. The Sydney Morning Herald and The Sun Herald reported that cartoonist Syd Nicholls attended the screening along with Eileen Alexander, who as a 21 year-old, played Madeline Twirt in the film. Eileen told how she was cast in the film after previously performing the lead role of Doreen in a touring stage production of The Sentimental Bloke, acting alongside Tal Ordell who played Ginger Mick.

Syd Nicholls and Fatty Finn

Fatty Finn is one of Australia’s most loved and longest-running comic strips, first published in The Sunday News as Fat and his Friends on 16 September 1923. The strip and the main character, in his trademark scout uniform, soon evolved into the familiar, knockabout young lad, and within a year the strip was renamed Fatty Finn.

The comic quickly gained popularity and, a little over three years later, film actor Tal Ordell decided to bring Fatty to the big screen. The introduction to The Kid Stakes shows Syd Nicholls himself at his drawing board, where his sketch of Fatty Finn comes to life. Young Fatty, looking at the drawing board asks, ‘What sort of a job have I got to do this week, Mr Nicholls?’ From here we are transported into Fatty’s world and the story unfolds.

Syd Nicholls was born in Tasmania, and lived for a time in New Zealand before moving to Sydney in his teens. His first cartoon was published when he was only 16, an attack on future Prime Minister Billy Hughes, in The International Socialist. Drawing controversial cartoons for radical publications including the International Workers of the World newspaper Direct Action, Nicholls rose to infamy through the publication of a cartoon critical of war loans that resulted in the publisher being prosecuted and sent to jail.

Nicholls became a regular contributor to The Bulletin from 1914, mainly with powerful anti-war commentary, while also studying at the Royal Art Society. In 1918, he was asked by film director Raymond Longford to draw the artwork for his new film The Sentimental Bloke. Nicholls’ whimsical illustrations alongside CJ Dennis’ verse on the intertitles add yet another dimension to that classic Australian film.

On The Kid Stakes’ relationship to The Sentimental Bloke, Paul Byrnes, writing for NFSA’s australianscreen website muses:

"[T]here’s little doubt that Fatty Finn … is highly influenced by CJ Dennis’ classic story of a sentimental tough guy from a poor inner-city neighbourhood. Fatty is a half-pint version of the ‘Bloke’ with his own ‘push’ of tiny would-be toughs and molls, who already have a strong sense of how the world works."

To add to the connection, director Tal Ordell (who had acted in films directed by Longford) shot The Kid Stakes in the same location, Woolloomooloo, as The Sentimental Bloke.

Joining Sydney’s Evening Standard newspaper in 1923, Syd Nicholls was asked to design a kids comic for the paper’s Sunday News. This was primarily to counter the popularity of Ginger Meggs in the Us Fellers strip (first published 1921), drawn by Jimmy Bancks in The Sunday Sun. And so, Fatty was born and continued to entertain readers for the next decade.

However, the merger of the once rival papers during the depression, along with editorial disagreements on the direction of the strip, saw publication of Fatty Finn cease in 1933. Nicholls then decided in 1934 to self-publish Fatty Finn’s Weekly (considered to be Australia’s first locally-produced comic book), but this lasted just a year. A decade later, in 1945, he again established a line of comic books featuring Fatty Finn, and the work of other Australian artists. Nicholls published other comics around this time, drawing adventure stories for older readers including The Phantom Pirate and Middy Malone, showcasing his great artistic skill, notably in the area of nautical themes.

By 1951, increased competition from imported and syndicated comics forced Nicholls to abandon his independent comics, and Fatty Finn returned to newspaper publication in The Sunday Herald. From here, Fatty and his gang took on the ever-changing world, while never aging themselves, for another quarter century. Syd Nicholls continued to draw Fatty Finn until his death in 1977.

Arthur Higgins and Woolloomooloo

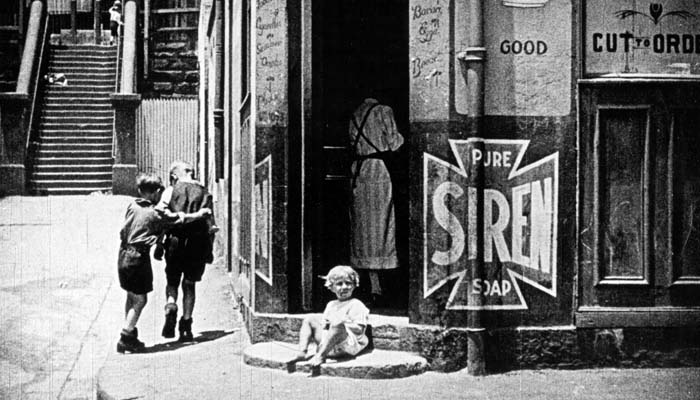

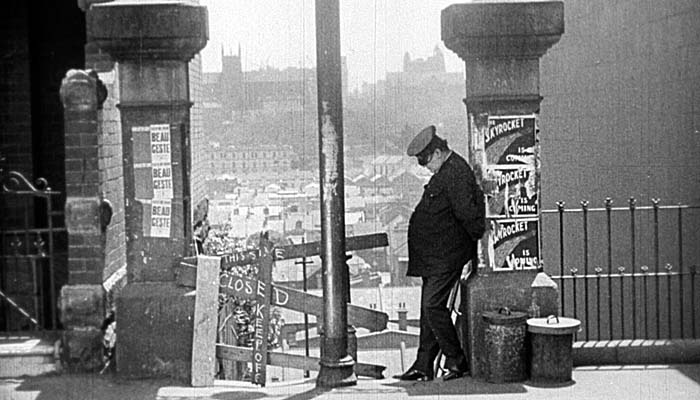

Renowned cinematographer Arthur Higgins’ poetic contribution to The Kid Stakes cannot be overstated. While following the exploits of Fatty Finn and his gang, he manages to also capture the flavour of working-class Woolloomooloo, with its tightly-packed terrace houses, back alleys, billboards, wharves and busy people. This low-lying dockside suburb facing a long, narrow bay sits separated from Sydney city by the raised parklands of The Domain, with Kings Cross and the mansions of Potts Point on its other side. Connecting these two worlds (at the time no roads joined the suburbs) are the steep stairs, down which poshly-dressed young Algie descends in search of friends, and later Fatty and the gang climb to retrieve Hector the goat from the mansion garden he has been devouring.

Tasmanian Arthur Higgins was one of three brothers, all of whom became cinematographers in the emerging new world of motion pictures. Higgins’ first film in the cinema boom year of 1911 (just five years after the world’s first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang) was The Fatal Wedding, the successful debut of both director Raymond Longford and leading theatre actress Lottie Lyell. Higgins worked mainly as a newsreel and documentary cameraman, while also teaming up with Longford (as did his brothers Ernest and Tasman), for most of his films.

During this period Higgins filmed The Tide of Death (1912), Australia Calls (1913), The Woman Suffers (1918), The Sentimental Bloke (1919), Ginger Mick (1920), On Our Selection (1920), Rudd’s New Selection (1921) and The Blue Mountains Mystery (1921), all working with Longford and Lyell. Fortunately, even with some 90% of silent films lost, enough of Higgins’ films survive today to confirm him as an exceptional cinematographer. With his eye as a cameraman of actuality and newsreel films, Higgins fully realised that while making a movie, he was at the same time documenting social history.

The Sentimental Bloke, based on the popular poems of CJ Dennis, directed by Longford, starring Lottie Lyell and shot by Arthur Higgins, is regarded as a masterpiece of Australian cinema. This film was made largely in Woolloomooloo, about a working-class bloke and his romance with the lovely Doreen, as was follow-up film Ginger Mick, also from CJ Dennis poems. Later, in 1922, Arthur Higgins filmed Sunshine Sally (almost a female version of The Sentimental Bloke, which also crossed the working class—Potts Point divide), once more in Woolloomooloo, for director Lawson Harris. So it’s fair to say he knew the territory!

As for all his other Woolloomooloo films, so much of daily Sydney life is on display in The Kid Stakes, framed by Higgins’ camera. He captures a way of life for working-class Sydneysiders: the corner shop, the side walls of buildings with painted advertising, and everyday workers of all descriptions. In the background of one scene a team of Clydesdale horses pull a dray piled with beer barrels; in another, ships are unloading at the docks. It is hard to imagine that these were all happy accidents, rather that the action was built around the location.

A scene from The Kid Stakes featuring a corner store.

The suburb in the 1920s, with its long finger wharf bisecting the narrow Woolloomooloo Bay, was home to the Sydney Fish Markets and a fishing fleet. Nets can be seen in some scenes and it is likely that many of the kids of Fatty’s generation are children of fishermen or wharfies. Being a disembarkation point for returning First World War soldiers, as well as arriving migrants, added to the diversity of the population. The late 1920s was also the era of Sydney’s notorious Razor Gang which was active in the area. The satirical parallels with Fatty and Bruiser’s rival gangs would have been obvious to the film viewers of the day.

Tal Ordell, an established actor but directing his first feature with The Kid Stakes, was able to rely on the experienced Higgins to shoot the film with his usual professional style, while he concentrated on directing the actors. Ordell’s regard for Higgins is clearly evidenced in the film titles, where Arthur Higgins’ cinematography is billed on the same screen as Tal Ordell’s own credit. High praise.

Arthur Higgins continued shooting films for many years to come. He transitioned to the new sound era shooting one of the very first Australian ‘talkies’ in Diggers (1931), then more films for Frank Thring (Snr) including three featuring slapstick comedian George Wallace. When he made his final feature film in 1946, Eric Porter’s stylish A Son is Born, he had been making films for 35 years.

Kids, goats and Queensland

Ordell—Coyle Productions: these words at the top of the opening title for The Kid Stakes give a clue to a couple of important aspects about the film, its funding, production, promotion and a not insignificant connection to Queensland. The production company is named for The Kid Stakes director Tal Ordell and Virgil Coyle. Queenslanders would be well aware of the Coyle name in relation to films — the cinema chain of Birch Carroll and Coyle (BCC) being the dominant exhibitor in the state.

Edward (EJ) Carroll, having pioneered open-air film screenings in Brisbane, was quite literally in at the start of feature film distribution, when he bought Queensland rights for The Story of the Kelly Gang, Australia’s (and the world’s) first feature film. Joined by his brother Dan, the Carrolls merged their company in 1909 with George Birch, who had established cinemas in Rockhampton, to form Birch and Carroll. Virgil Coyle, hotel and cinema owner of Townsville, joined the partnership in 1923 to form BCC, which at that time ran 13 cinemas in seven towns.

BCC then expanded, opening their grandly appointed Brisbane Wintergarden Theatre in 1924, designed by architect Henry White as both a cinema and live performance venue. More 2,000-seat Wintergarden theatres in Ipswich, Rockhampton, Townsville, Maryborough and Bundaberg followed, adding to their existing cinemas. White also designed Sydney’s magnificent Rose Bay Wintergarden Theatre (1928) for EJ Carroll.

The script of The Kid Stakes called for Fatty to enter his goat Hector in billy-cart races against his rival Bruiser. However, with goat races illegal in New South Wales, the solution was to film in Queensland. Through producer Virgil Coyle, plans were made to film the race scenes at Rockhampton Showgrounds on Saturday 5 February 1927, as part of regular goat races held in the town. Coyle’s interest in the film, helped naturally by his own chain of cinemas, played its part in the original financing, the filming and the ultimate success of this classic Australian kids’ film.

An excerpt from The Kid Stakes (1927). Watch excerpts of the film and read more about it on the NFSA’s australianscreen website.

BCC assisted with publicity for the filming with an article in The Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, talking about the film, inviting participants and listing a program which, in addition to goat races, ‘will include trotting, cycling, motor cycling, foot-running and school boys’ relay races’. To ensure good attendance, admission was only one shilling, and sixpence for kids. ‘Mr. Ordell is desirous of a roll-up of 50 goats. There will be no nomination fee or admission charge for boys taking part in the goat races.’

The article notes that for the actual goat race, ‘the Kid Stakes’, ‘Messrs. Birch, Carroll, and Coyle have donated … a special prize of 1 pound 1 shilling and a sash for the winning goat in the big Kid Stakes race.’

The following week, under the headline, ‘Goats galore for Kid Stakes film’, The Morning Bulletin reported the successful day’s events:

"The goat stables of Rockhampton must have been a scene of feverish activity on Saturday morning last. Indeed, it would not be surprising to hear that the railway livestock bookings had soared appreciably on account of the inrush of billies anxious to figure in the finale of the great Australian goat film, The Kid Stakes. More than 60 horned quadrupeds, with spiders of every description, crowded the saddling paddock at the show grounds, and some of the racing was very fast and hilarious."

"Mr Tal Ordell, producer of the film, expressed himself as delighted with the keen afternoon’s sports. The crowd was as large as Mr Ordell could have desired for his ‘exciting finish’ scenes … When requested by Mr Ordell, the stands rose to a man and cheered wildly, the cameraman recording their enthusiasm."

The goat race finishing line

The article then goes on to report the results of the actual goat race, and the sash presentation to the winner by The Kid Stakes director Tal Ordell and his son ’Pop’ (Fatty):

"In goat circles the event of the day was the comeback of the original champion, Owens’ Koongal, after his enforced rest suffering from a dog bite. Koongal’s off leg was bandaged, but judging by his performances, his recovery is practically complete, and he must have been well trained. In the First Division, off the five yards mark, he snatched victory from game little Kavett (scr.) by about the length of his start, the time being 1 min. In the special race for The Kid Stakes champion sash, both goats started from scratch. Kavett got away better than Koongal, who tried his old game of running inside the track, where the going on Saturday was very heavy."

"Entering the straight the goats were almost together, and the white goat appeared to swing down, cutting Kavett off. The little black, however, worked round, and made a magnificent finish, literally leaping to reach the post a head in front of the old champion. Later Murphy, Kavett’s driver, was decorated with the champion sash by Mr Ordell, assisted by the hero of the forthcoming production, little ‘Pop’ Ordell. The time for this race was 57 4/5, a track record."

The Kid Stakes returned once more to Rockhampton when the finished film screened at both the Wintergarden and Earl’s Court Theatres from 17 September 1927, as star attraction for the Saturday matinee.

Over the course of the decade, BCC theatre managers had become masters at staging stunts to publicise their latest (usually Hollywood) movie, with competition between different theatres for the best box office return or outrageous stunt.

While some Queensland cinemas staged goat races outside the theatre to promote The Kid Stakes, at the Wintergarden Theatre in Townsville a month after the Rockhampton screenings, BCC promoted the film with the novel attraction of live goat races in the theatre — 12 laps of a special course on the new Wintergarden’s well-proportioned stage (described by one visiting theatre company as ‘daunting’).

A generous first prize of three pounds was offered, along with a one pound prize in a separate competition for best ‘turned-out’ goat!

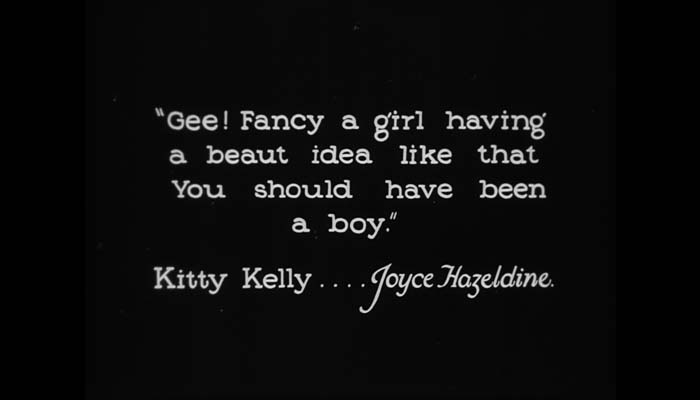

Slang terms used in the intertitles

| Alleys, glassy, stinkies | types of marbles |

| Bonzer | really fantastic |

| Beaut | beautiful – excellent, terrific |

| Cock-eyed fish | dumbest of the dumb, looking at things cross-eyed |

| Copper | policeman |

| Dot yer blinkin’ eye | give someone a black eye by punching them |

| Headlights (Hogan) | kid who wears glasses (called Hogan) |

| Jack Gregory | Australian cricket all-rounder, famous for big hitting |

| Macartney | Charlie Macartney — flamboyant cricket batsman |

| Mailey | Arthur Mailey – Australian cricket spin bowler |

| No savee | I don’t understand, speaks a different language |

| On the rails | on the inside lane of a race track |

| Pepper | style of rope skipping — very fast |

| Right oil | a tip or information |

| Sheik | a popular romantic film character played by Rudolf Valentino |

| Silly point | cricket close fielding position |

| Sixer | hit the ball over the fence — scores six runs |

| Spare me days | give me a break, don’t give me grief |

| Turps | turpentine — used on the whip to make the goat run faster (cheating) |

NFSA behind-the-scenes

In the mid-1950s and early 1960s, the then National Film Archive within the National Library of Australia received four 35mm film prints of The Kid Stakes — three on original 1927-era volatile nitrate film and one 1950s acetate ‘safety’ film – from three different sources. The film prints were of varying lengths and not all were complete. The best quality and complete print was determined to be the acetate print, and this preservation master has been used as the basis for all subsequent duplication of the film, including 16mm reduction prints, 35mm cinema prints and video transfers that have been available for screenings for the last 50 years.

In recent years, 35mm film projectors have all but disappeared from cinemas. The task of bringing The Kid Stakes from the 1920s era of silent, 35mm projection off nitrate film stock into the current age of digital cinema projection, is one that has involved many of the NFSA curatorial and specialised technical areas.

In the initial stage of the project, existing 35mm film preservation components of The Kid Stakes were assessed, resulting in the original picture duplicate negative being selected as the master to use for the transfer. This negative had been produced by the NFSA’s Motion Picture Laboratory from the original 1950s acetate print received by NFSA.

To telecine, or transfer the negative from 35mm film to high-definition (HD) video, the telecine and 2K colour correction system was used. Working at a Blu-ray equivalent resolution of 1080p, the system digitally ’flipped’ the negative into a positive image.

The telecine process required each individual shot in the film to be graded – a process where the operator visually assesses and adjusts the colour levels for each scene in the picture. In the case of this black-and-white film, the contrast between the whites, greys and blacks was improved to provide maximum clarity of image and consistency from shot to shot. This involved a week of grading, totalling around 700 grades for the whole feature. Each intertitle was graded to ensure it matched the live-action scenes when viewed on a large screen. Some of the live-action scenes also had issues in that the black-and-white contrast in close-ups was not matching wide shots: some black levels were too high and whites were brought down in scenes to enhance the details in peoples’ clothing and background areas.

The film was run at 18 frames per second (fps) through the telecine, but the HD output was converted to 24fps via a process of interpolation — inserting duplicate frames. This maintained the correct speed of the film, especially during the many panning shots in the film which remained smooth with no skipping and ensured the pre-requisite 24fps was delivered for Digital Cinema Package (DCP) creation purposes. Normally, this is hard to achieve with a computer system due to the processing power and rendering time required, but the telecine system delivered the result utilising a real time process.

Once the grade was complete, the film was transferred to hard drive. Further processing occurred to create the DCP to be used for cinema projection. Many test screenings were held in the NFSA’s Arc cinema and adjustments made to fine-tune the film. The digital cinema premiere screenings took place in Canberra and Sydney in June and August 2015. Both presentations featured live musical accompaniment composed and performed by Jan Preston.

Jan Preston’s musical piano score was recorded by the NFSA ahead of the premiere Canberra performance. The recording session in Arc cinema was live — lacking only an audience — but allowing for optimal microphone placement and adjustments for levels without time constraints. Once all was ready, Jan played her score on the grand piano while watching the film projected up on Arc’s cinema screen. She performed it in one single, continuous 76-minute take.

The NFSA then mastered the recording to produce an optimised stereo mix. The soundtrack file was synchronised and combined with the visual grade created for the DCP to create the final HD master. While the DCP master matched the specifications for HD Blu-ray at 24fps, the file for the DVD needed to be reformatted to Standard Definition (SD) and pitch corrected to the required 25fps. Authoring for both the Blu-ray and DVD were carried out by the NFSA.

All told, some 15 NFSA specialist staff were involved in the process to produce the DCP, Blu-ray and DVD. The Kid Stakes is now another classic Australian film available for cinemas to screen in the digital era and be enjoyed by a new generation.

The music: Jan Preston’s piano score

The NFSA is delighted to feature the piano accompaniment of Jan Preston on the 2015 DVD and Blu-ray release of The Kid Stakes. Jan has been performing to the film for a number of years, generating a vibrancy and energy with her music that matches the film’s charm. Jan’s solo piano score was recorded in the NFSA’s Arc cinema in Canberra, ahead of the public screening to launch the NFSA’s high-definition digital transfer of The Kid Stakes, on 19 June 2015.

Jan Preston at the piano

Jan Preston:

"I fell in love with The Kid Stakes the first time I saw it and have never tired of performing to it. My entire musical motivation comes from the film which I watch throughout while playing. In essence it’s a kids film with a sunny and comic disposition, so I felt it was important to match this tone with major keys and straightforward melodic musical themes. I avoided dark or complicated harmonies (only 1 or 2 diminished 7th chords throughout) and used authentic pianistic styles of the time including ragtime, waltz and swing boogie."

There are 5 themes on which I improvise:

Fatty’s Theme

Bruiser’s Theme

Horatio’s Love Waltz

The Policeman’s Theme

The Race

"For the goat race scenes I use elements of the exciting 8-to-the-bar driving left hand characteristic of boogie, and upward modulations so that it all peaks at the end. It’s rather strenuous to play!"

Jan Preston is Australia’s foremost boogie and blues pianist, performer and composer. Winner of five music awards, she plays festivals and concerts throughout Australia, New Zealand, the UK, Europe and China, tours her own shows and writes music for films and television. Composing for silent movies is one of Jan’s great loves, and she has performed her original scores for classic silents including Fritz Lang’s The Spy, Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy, and Ernst Lubitsch’s So This is Paris.

Credits

The Kids

| Fatty Finn | Robin ‘Pop’ Ordell |

| Tiny King | Charles Roberts |

| Bruiser Murphy | Frank Boyd |

| Shooey Shug | Edward Stevens |

| ‘Seasy | Billy Ireland |

| Headlights Hogan | Stanley Funnelle |

| Betty Briggs | Gwenda Hemus |

| Kitty Kelly | Joyce Hazeldine |

| Master Algie Snoops | David Lidstone |

| Molly Kelly | Evelyn Rawle |

| Jimmy Kelly | Ray Salmon |

The Adults

| Constable Claffey | Leonard Durell |

| Horatio Wart | Jimmy Taylor |

| Madeline Twirt | Eileen Alexander |

| Mr Twirt | Tom Cannan |

| Race Commentator | Tal Ordell |

| Syd Nicholls | himself |

Further reading

Donaldson, David 2015, ‘How They Rescued The Kid Stakes’, 4:3 website (4 August 2015)

Freebury, Jane 2015, ‘Jan Preston’s bonzer score for The Kid Stakes’, The Canberra Times (12 June 2015)

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.