Preserve or re-create?

Conservators can no longer think solely about the longevity of the tangible object. We must also strive to preserve the intangibles: the meaning of the object, its purpose, the intended settings it was created for and role it was made to play. Figuring out how to factor in the intangibles, how to preserve the non-physical elements surrounding physical objects, will be a key challenge in the years to come. It’s also an example of how conservators must constantly defy the assumptions of their profession for their work to remain relevant to the public.

At a recent conservation conference Samuel Jones from the British think-tank Demos presented a session entitled ‘Conservation in a Time of Change – The Ethics of Care’. He spoke about the many challenges that the conservation profession faces and how we need to make ourselves relevant in the public eye. There were many important insights shared through this presentation, particularly in relation to public perceptions about conservation:

We need to change the public notion that conservation is something that goes on behind closed doors, in a lab, and with things that people aren’t allowed to touch. We need to find the way to connect with people and our profession, the caring of the cultural materials.

Mr Jones also made a significant point about the role of conservators within society:

Conservators don’t just fix things when they are broken; they stand for a wider social ethos of care, in which we individually and collectively take responsibility and action. Heritage and conservation are part of an ethics of responsibility and means of connecting with deeper values. They also play a vital role in building a greater awareness of the cultures around us and valuing of things past and present, for the benefit of now and the future.

He included many examples to address the point of public involvement, including the story of the Cerne Abbas Giant in the UK.

Cerne Abbas Giant. Image by Nigel Mykura made available under Creative Commons.

The outline of the Cerne Abbas Giant had been maintained by the grazing of sheep belonging to a local sheep farmer, a practice allowed by the National Trust UK that ended when the farmer became bankrupt. Faced with the time-consuming and labour-intensive challenge of trimming the grass outline of the 180-foot giant, the National Trust called for volunteers. Surprisingly, people came from far and wide to assist. One volunteer made a 500-mile round trip to help, explaining that ‘It’s hard work … but it’s not often you get to work on an icon’. It is this sense of community ownership of our heritage and culture that will support our profession into the future.

It is no longer enough to only be concerned with the longevity of objects, art or buildings. As a profession, we need to constantly question what we are conserving, and for what purpose. What does conservation mean in a broad context, and most importantly what does it mean to the public?

An Australian conservation issue heating up in Melbourne brings to the fore many of these issues. Susanna Collis from Heritage Victoria chaired a discussion at the conference about the conservation of a Keith Haring mural in Melbourne which is fading badly, paint slowly flaking off the brick wall (see examples of Haring’s work at Artsy). The mural has lost its original vibrancy of colour and is barely visible from a distance. It is one of the few surviving original Keith Haring murals in the world that has not been restored and the last mural that he painted himself. The Keith Haring Foundation, which is organised to sustain and protect his legacy, argues that the surface of the mural should be repainted to restore its original colour and vibrancy, as does the Save Melbourne’s Keith Haring Mural group. The alternative proposed by a group of conservators is a Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for the wall, preserving the original Keith Haring painting in its current faded state. This preservation could halt or slow down more fading with some ongoing maintenance. This caused really interesting debate because normally as conservators we would agree on the CMP proposal of preserving the original – but would this preserve the purpose of the mural work and what it means to the people of Melbourne? Unfortunately Keith Haring is no longer with us to specify his wishes for the mural. Would he have preferred it to eventually fade away or be restored to its original look?

The robust panel discussion saw the conference attendees questioning the ethics of conservation as we traditionally understand it. There was a strong sense of trying to understand and challenge current thinking, as well as redefining conservation ethics. The discussion surrounding this mural was a perfect example of how conservators can connect their work to the community, in this case the people of Melbourne.

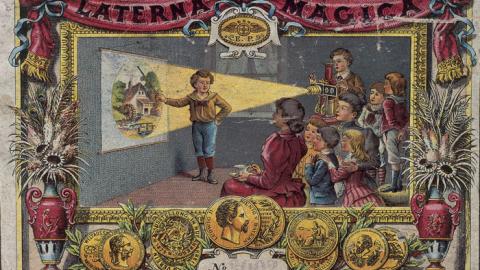

An example from the NFSA is the recent work that I carried out involving the preservation and digitisation of mechanical glass slides. The cleaning and digitisation work will enable the wider community to access these images online. A forthcoming video showcases the beauty and the different moving mechanisms of these slides. In making the video, we projected a few of these mechanical glass slides using a projector that was fitted with a light bulb. The colours and the movement of the slide mechanism were part of the experience of watching the slides projected which could not be reproduced using a digital image on a computer screen.

As conservators it is our duty to preserve these mechanical slides and projectors. We have digitised the images to limit access to the original works and allow widespread access to the slide images. By limiting access to the original objects and storing them in climate-controlled rooms, the slides will be preserved for longer. But it is important that we examine our purpose in doing this. If these slides are never viewed again in their original context, how can we preserve the magical experience of viewing them projected on a wall? After seeing them projected, my wish is that more people have the privilege of viewing these slides projected, as the viewing experience was originally intended.

These ethical dilemmas, as well as trying to redefine and connect our work to the wider public, are ongoing challenges facing a profession that attempts to ‘preserve’ objects in a constantly changing society.

Shingo Ishikawa attended The Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Materials National Conference in Canberra, 19-21 October 2011.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.