Stanley Hawes

On 26 February at the State Library of South Australia the NFSA will present a Stanley Hawes Retrospective as part of DocWeek’s Australia’s Living Memory, a tribute to the output of Film Australia and to Australia’s federal government film production dating back to 1913.

The Hawes retrospective will consist of two films closely associated with the organisation’s first Producer-in-Chief, Stanley Hawes (1905-1991): School in the Mailbox (1946), which Hawes directed, and The Queen in Australia (1954), which he produced. In the following blog, NFSA’s Manager, Access Projects, Graham Shirley, shares his memories of and information about the life of Stanley Hawes.

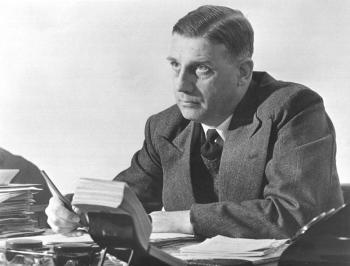

Stanley Hawes was always, for me, a figure who radiated authority on the one hand and a gentle courtesy on the other. He could, with his eyes twinkling, invest an anecdote with dry wit, and within minutes recall the pain and frustration he had felt when debating with government bureaucrats who claimed that no government film should exceed the brief of bland publicity. For Hawes, who knew filmmaking inside-out and had strong views about the moral responsibility of filmmakers, such views were anathema.

Recording a video interview with Stanley Hawes for the Australian Film, Radio and Television School in 1986 gave me insight into the ways he thought and worked. Having already supervised (which, in effect, meant produced) over 500 films in his 24 years as Producer-in-Chief of the federal government’s film unit, Hawes approached this autobiographical project with the kind of hawk-eyed scrutiny that I assumed he had applied to many of those 1946-1970 documentaries. Before we recorded, he gave feedback on my list of questions, then wrote detailed draft replies. He viewed a rough-cut, then the fine-cut of the completed interview, urging that AFTRS incorporate more than the rough-cut had on events in his career before 1940.

In our day-to-day dealings on the project, I found Hawes to be collaborative and respectful, although there were flashes of the unyielding will that had ensured his survival throughout his career. We were both at that time regular attendees at the Sydney Film Festival, and in conversation there and elsewhere, he revealed a prodigious knowledge of international film history. But if he didn’t like a film or TV program, as I found when I casually mentioned the topic of the ABC mini-series Scales of Justice (1983) which tackled police corruption, his verdict could be swift and explosive.

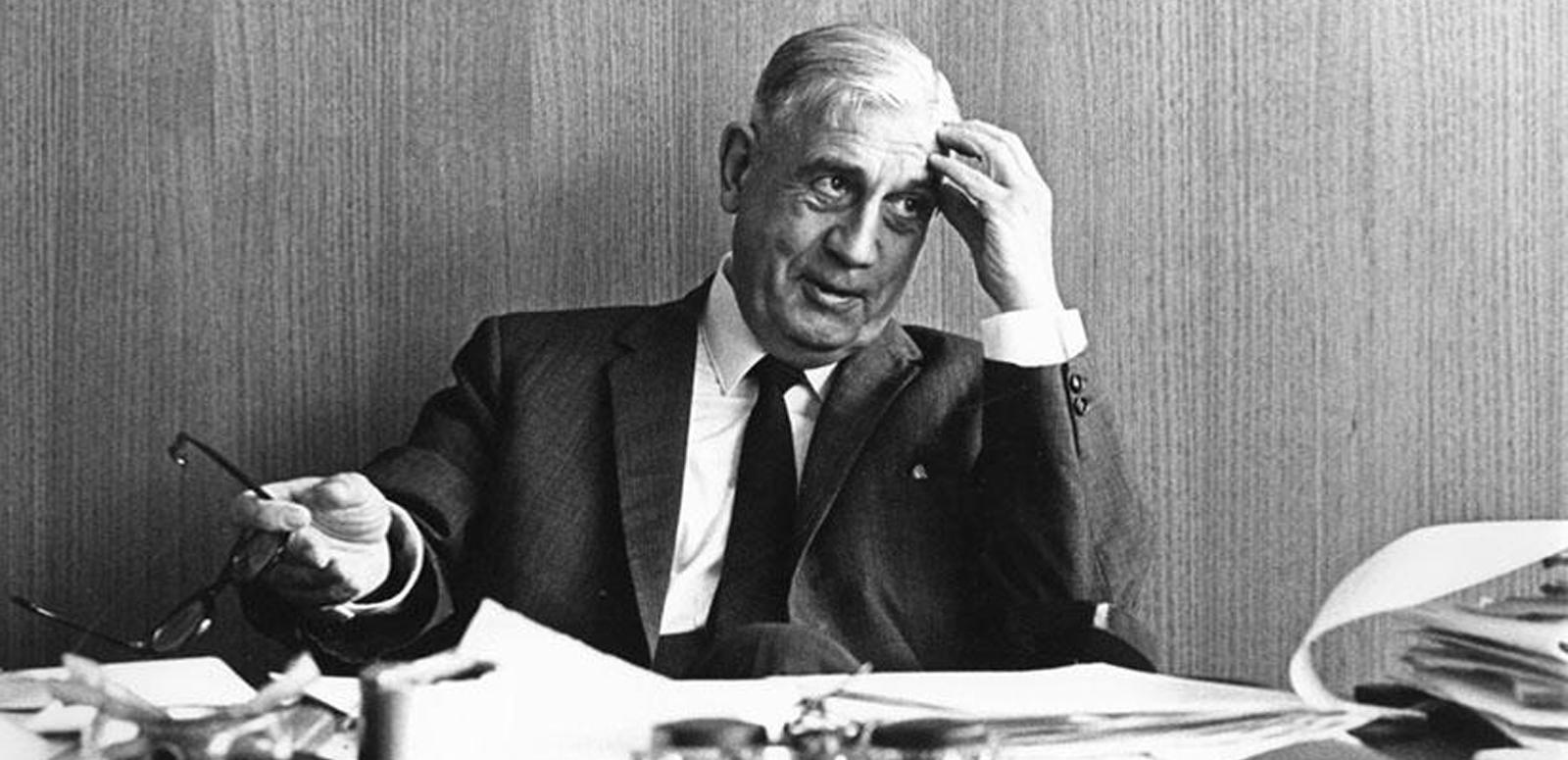

Cinematographer Reg Pearse (left) on location with Producer-in-Chief Stanley Hawes, 1955

Stanley Gilbert Hawes was born in London on 19 January 1905 to Gilbert and Helen Hawes (nee Foxall). During his time as a student at Christ’s Hospital School he became absorbed in the world of theatre, and from 1922 to 1934, while working for the City of Birmingham Corporation, he was an amateur actor with the Birmingham Municipal Players. In his early 20s he became passionate about film, and he was one of the founders of the Birmingham Film Society, marrying one of the society’s co-founders, Jessica Ragg in 1932. In the mid-1930s they moved to London, where Hawes worked for documentary production companies including Gaumont-British Instructional Films, where he was mentored by filmmaker Paul Rotha. In 1936 Rotha and Hawes moved to the Strand Film Company, and it was there that Hawes built up his reputation as a director of documentaries, the best known of which was Monkey into Man (1937). Between 1940 and 1946 Hawes produced and directed many films for the National Film Board of Canada, while working to John Grierson, the organisation’s commissioner, whose highly influential views of the ideal ‘classical’ documentary Hawes shared.

In May 1946 Hawes and his family moved to Sydney, where he became Producer-in-Chief of the Film Division of the Australian National Film Board, which had been formed in April 1945. Becoming absorbed in the running of the division, Hawes hardly ever directed films after 1946, although School in the Mailbox (1946), one of the films he did make, was nominated in 1948 for a US Academy Award for Documentary (Short Subject). His greatest creative achievement of the 1950s was to supervise the country’s first fully Australian-funded feature-length colour film, The Queen in Australia (1954), which drew its heart and soul from focusing on the impact of the 1954 royal tour on ordinary Australians.

Hawes’ documentary preference remained its classical form rather than the dramatisation, cinéma vérité and innovation favoured by others. Films that challenged social and political conventions were, in Hawes’ opinion, unwise for the Film Division, which became the Commonwealth Film Unit (CFU) in 1956. One of Hawes’ persistent memories of the ’50s was travelling endlessly between Sydney and Canberra to keep the unit politically afloat at a time when independent producers were lobbying the government to abolish the unit and turn all of its production across to them. Individualistic and talented filmmakers like John Heyer, Lee Robinson and Colin Dean who had created a fresh start for Australian documentary at the unit from the mid-1940s, had left the organisation by the mid-1950s. The late 1950s, dominated by films for government departments and government inquiries into the CFU, is often seen as a period of creative atrophy for the unit.

In the 1960s, when the CFU started recruiting younger producers and directors, the organisation began to make films that reflected that decade’s social and cultural change. From the Tropics to the Snow (1964), which Hawes executive produced, was semi-dramatised, stylistically adventurous and presented a satire on filmmakers trying to break away from a conventional style of all-embracing films about Australia that federal filmmakers had made for decades. At the unit in the 1960s, Hawes also made it possible for Ian Dunlop to embark on a new, personalised approach to ethnographic filmmaking.

In 1970 Hawes supervised the unit’s production of a technically challenging multi-screen, 360-degree film for the Australian Pavilion at Osaka’s Expo 70. That same year he was awarded an MBE and the Australian Film Institute’s Raymond Longford Award. After his retirement in April 1970, Hawes remained active in film issues, chairing the National Film Theatre of Australia for five years and the Cinematograph Film Board of Review for six. His last production credit was as producer of The Challenging Years (1979), a documentary about retirement planning. Since 1997 the annual Stanley Hawes Award has been presented to a person or organisation who, over a period of time, has made an outstanding contribution to documentaries in Australia.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.