WARNING: this article may contain names, images or voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

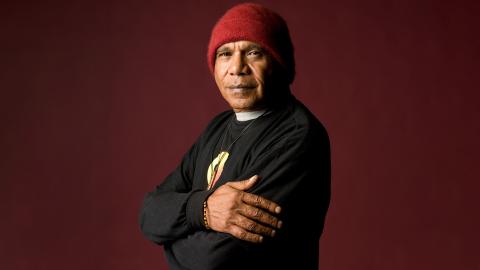

In 2017 the NFSA screened the colonial-era drama The Tracker (2002) and hosted a Q&A afterwards with maverick Australian director Rolf de Heer in which he spoke about the film’s influences, production and legacy: